When a generic drug hits the market, you might wonder: is it really the same as the brand-name version? The answer lies in two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab jargon-they’re the foundation of how regulators decide if a generic drug is safe and effective. If these two values match closely between the original and the copy, the generic can be approved without running expensive clinical trials on thousands of patients. Here’s how it actually works.

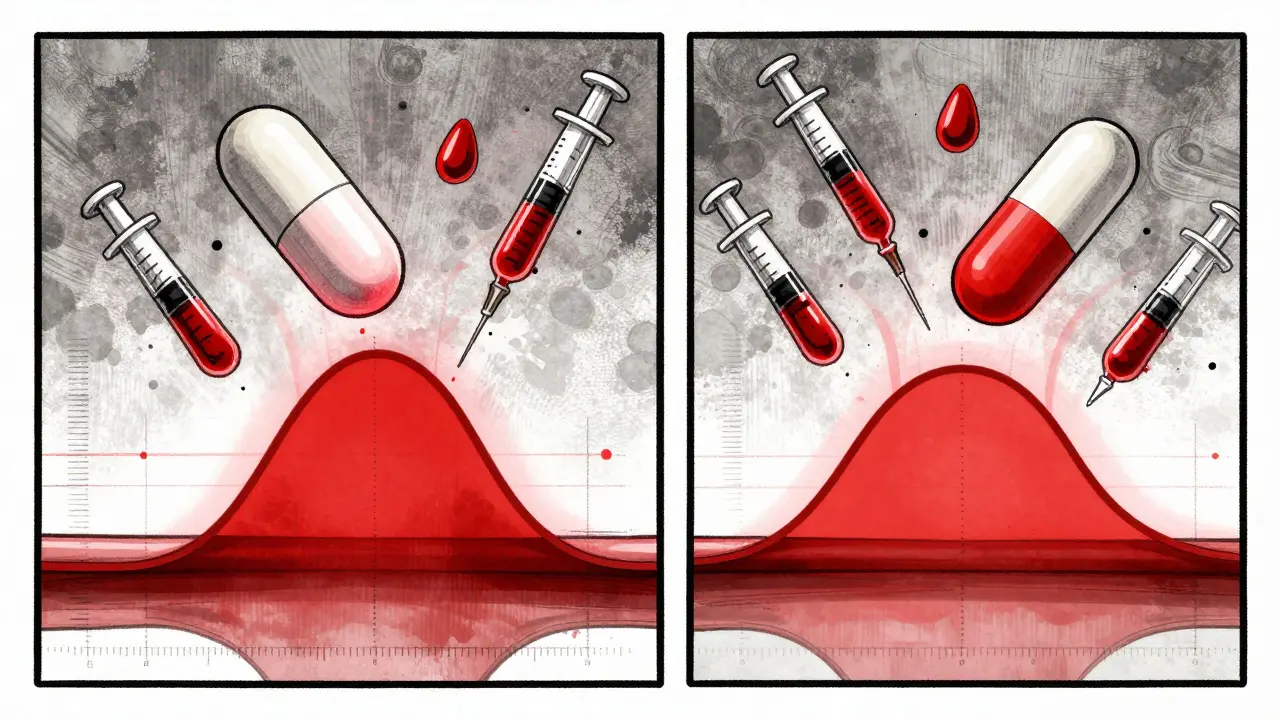

What Cmax Tells You About Drug Absorption

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It’s the highest level of a drug in your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a wave-how high does the drug rise before it starts to fall? This number is measured in milligrams per liter (mg/L) and tells you how fast the drug gets into your system.

For some drugs, the speed of absorption matters a lot. Take painkillers like ibuprofen or naproxen. If the Cmax is too low or too slow, you won’t feel relief quickly. On the flip side, for drugs with a narrow safety margin-like warfarin or digoxin-a Cmax that’s too high could cause dangerous side effects. That’s why regulators don’t just care about the total amount of drug you get-they care about how fast you get it.

In a typical bioequivalence study, blood samples are taken every 15 to 30 minutes in the first few hours after dosing. Missing even one key sample during this window can throw off the Cmax reading. Studies show that about 15% of failed bioequivalence tests happen because sampling wasn’t frequent enough early on. That’s why modern labs use precise timing-not just scheduled times like “2 hours after dose,” but the exact time each sample was drawn. Real-world data matters.

What AUC Measures: Total Exposure Over Time

AUC means area under the curve. It’s the total amount of drug your body is exposed to from the moment you take it until it’s mostly cleared. Imagine plotting drug concentration in your blood over 24 hours. AUC is the space under that curve. It’s measured in mg·h/L-how much drug is in your system, multiplied by how long it stays there.

This is critical for drugs that work based on total exposure. Antibiotics like azithromycin, or antidepressants like sertraline, rely on staying at a certain level in your blood over hours or days. If the AUC is too low, the drug won’t work. If it’s too high, you risk toxicity. AUC doesn’t care when the peak happens-it cares about the full journey.

Regulators look at two versions of AUC: AUC(0-t), which covers the time until the last measurable concentration, and AUC(0-∞), which estimates total exposure including the tail end where the drug is almost gone. Both are used, depending on the drug’s half-life. For most immediate-release tablets, AUC(0-t) is enough. For longer-acting drugs, they need the full picture.

The 80%-125% Rule: How Close Is Close Enough?

Here’s the golden standard: for a generic drug to be approved, the ratio of its Cmax and AUC to the brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand-name drug has a Cmax of 10 mg/L, the generic’s Cmax must be between 8 and 12.5 mg/L. Same for AUC.

This range isn’t random. It comes from decades of statistical analysis and real-world outcomes. The FDA and EMA adopted it in the 1990s after reviewing thousands of cases. On a logarithmic scale, 80% and 125% are symmetric around 100%-ln(0.8) = -0.2231 and ln(1.25) = 0.2231. This works because drug concentrations in the blood don’t follow a normal bell curve; they follow a log-normal distribution. So, you have to log-transform the data before running the math.

And here’s the kicker: both Cmax and AUC must pass. If one is within range but the other isn’t, the drug fails. You can’t say, “Well, the total exposure is fine, so the peak doesn’t matter.” That’s not how it works. Both are non-negotiable.

Why Both Metrics Are Non-Negotiable

Some people think AUC is the only important number. After all, it’s the total exposure. But that’s misleading. Two drugs can have the same AUC but wildly different Cmax values. One might spike quickly and crash fast. The other might rise slowly and stay steady. For a drug like metoprolol, used for heart conditions, a rapid spike could cause dizziness or low blood pressure. A slow rise might be safer.

Dr. Donald Birkett, a leading clinical pharmacologist, put it simply: “AUC reflects total exposure, which drives efficacy. Cmax reflects the rate of absorption, which drives safety.” That’s why regulators insist on both. It’s not just about whether the drug works-it’s about whether it works safely.

Take a real example from a 2007 BPJ study: Brand-name Drug A had a Cmax of 8.1 mg/L and AUC of 124.9 mg·h/L. Generic Drug B had a Cmax of 7.6 mg/L (94% of the brand) and AUC of 112.4 mg·h/L (90% of the brand). Both fell within the 80%-125% range. The generic was approved. No clinical trial needed. Just solid pharmacokinetic data.

When the Rules Get Tighter

Not all drugs follow the 80%-125% rule. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where even small changes in exposure can cause harm-regulators tighten the limits. For drugs like levothyroxine, warfarin, or cyclosporine, the acceptable range is often narrowed to 90%-111%.

The EMA explicitly recommends this tighter range for these high-risk drugs. The FDA doesn’t mandate it universally but allows sponsors to request it based on data. Why? Because a 10% difference in levothyroxine can push a patient from underactive to overactive thyroid. That’s not just a lab number-it’s a hospital visit.

There’s also the issue of high variability. Some drugs show wildly different levels in different people-even when they take the same dose. For these, the standard 80%-125% range might be too strict. The EMA allows something called “scaled average bioequivalence,” which adjusts the range based on how variable the drug is. But this is controversial. Not all regulators accept it. The FDA does, under specific conditions. It’s a balancing act between science and safety.

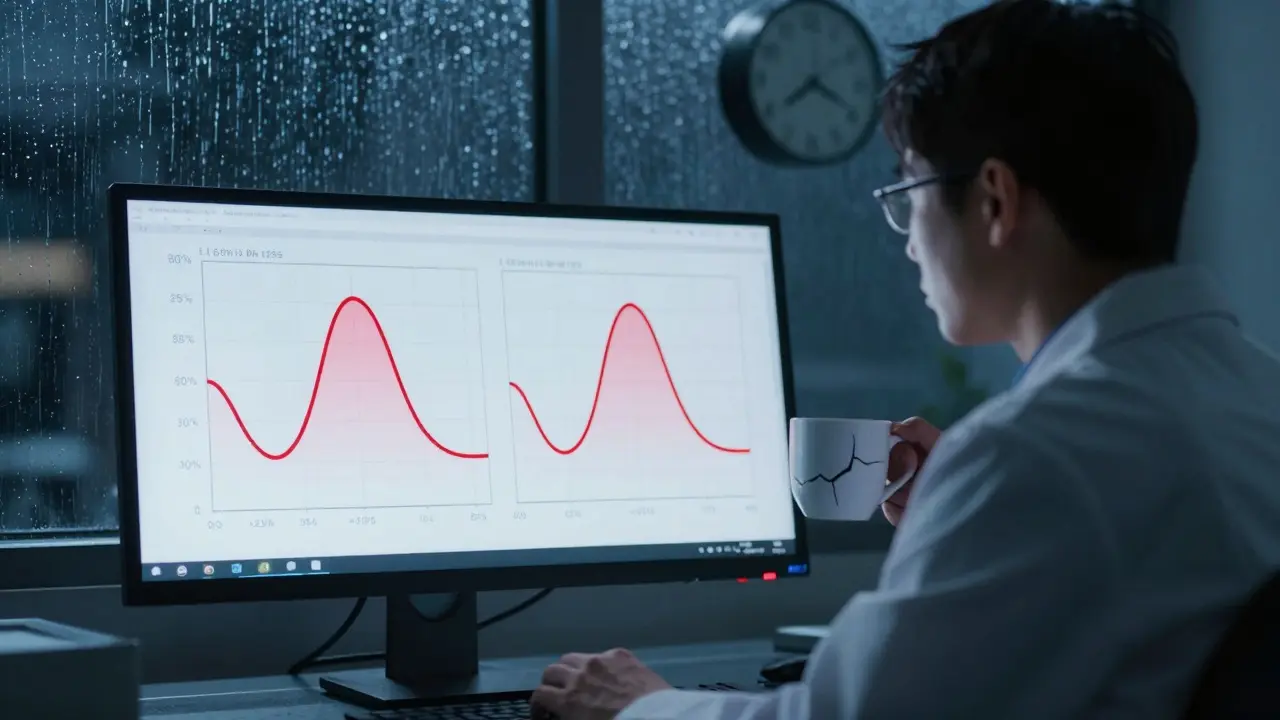

How These Studies Are Actually Done

A typical bioequivalence study involves 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. They’re given the brand-name drug one time, then the generic another time, with a washout period in between. Each person serves as their own control. Blood is drawn 12 to 18 times over 24 to 72 hours, depending on the drug’s half-life.

The samples are analyzed using LC-MS/MS-liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. This method can detect drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. That’s one-billionth of a gram. Without this sensitivity, we couldn’t measure low-dose drugs like levothyroxine or hormonal contraceptives accurately.

Studies are usually done in a controlled setting. Volunteers fast overnight, drink water, and avoid caffeine or grapefruit juice. Everything is standardized. Why? Because food, activity, or even stress can change how a drug is absorbed. If you want to compare two products fairly, you have to control the variables.

Most studies use a two-period, two-sequence crossover design. Half the group gets the brand first, then the generic. The other half gets the generic first, then the brand. This cancels out individual differences in metabolism.

What Happens When a Study Fails

Not every generic passes. When a bioequivalence study fails, it’s usually because of one of three things:

- Sampling was too sparse during the absorption phase, so Cmax was inaccurate.

- The formulation had unexpected excipients that slowed or sped up absorption.

- The drug had high variability, and the 80%-125% range was too tight.

When this happens, the manufacturer has to go back to the drawing board. They might reformulate the tablet-change the binder, the coating, or the particle size. Sometimes they need to run a new study with more frequent sampling. It’s expensive. That’s why many generic companies invest heavily in formulation science before ever running a trial.

According to industry data, about 90% of bioequivalence studies now use software like Phoenix WinNonlin to analyze the data. These programs handle the log-transformation, calculate confidence intervals, and generate the statistical reports regulators demand. Processing one study takes 2-3 days. But the science behind it? It’s been refined over 40 years.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Over 1,200 generic drugs were approved in the U.S. in 2022 alone. Nearly all of them relied on Cmax and AUC data. The global bioequivalence testing market is worth over $2 billion and growing. Why? Because generics save billions in healthcare costs. But those savings only work if the generics are truly equivalent.

A 2019 meta-analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine looked at 42 studies comparing generic and brand-name drugs. It found no meaningful differences in effectiveness or safety-as long as the drugs met the bioequivalence criteria. That’s powerful evidence. The system works.

Even so, regulators are evolving. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance suggests using partial AUC for complex modified-release drugs-like those that release medicine in two phases. The EMA is pushing for tighter limits on high-risk drugs. But the core hasn’t changed. Cmax and AUC remain the gold standard.

As Dr. Robert Lionberger of the FDA said at a 2022 conference: “AUC and Cmax will remain the primary endpoints for conventional drugs for the foreseeable future.” Why? Because they’ve been validated by decades of real-world use. They’re simple. They’re measurable. And they’ve saved countless lives by making safe, effective drugs affordable.

What You Should Know as a Patient

You don’t need to understand the math. But you should know this: when your pharmacist gives you a generic, it’s been tested. Not just for purity or cost-but for how your body actually handles it. The same peak. The same total exposure. The same safety profile.

If you’ve ever switched from a brand to a generic and noticed a change-like feeling more tired, or your condition acting up-it’s worth talking to your doctor. But statistically, it’s far more likely that your body adjusted, or something else changed. The science behind bioequivalence is solid. The system is designed to catch the outliers before they reach you.

So next time you pick up a generic prescription, remember: behind that label is a rigorous, science-driven process. Two numbers. One goal. Safe, effective, affordable medicine for everyone.

Juan Reibelo

January 23, 2026 AT 13:32Cmax and AUC? Yeah, I’ve seen this in med school, but honestly? It’s wild how much math goes into something as simple as a pill.

One wrong formulation, and you’re not just getting a weaker drug-you might get a dangerous one.

Respect to the pharmacologists who nail this stuff.

Kat Peterson

January 25, 2026 AT 04:26OMG I just realized… generics are basically the TikTok remixes of real medicine 😭

Same beat, but someone messed with the bass and now your heart’s doing the cha-cha 🤯

Also, who approved this?? 😳

Himanshu Singh

January 25, 2026 AT 11:21This is beautiful. Science doesn’t need drama to be powerful.

Two numbers-Cmax and AUC-hold the balance between life and risk.

It’s like poetry written in pharmacokinetics.

Every milligram per liter, every hour under the curve… it’s a silent promise to patients.

We forget that behind every generic pill is a lab, a researcher, a sleepless night.

Thank you for reminding us.

Not everyone gets to see the quiet heroes of healthcare.

Keep shining light on this.

It matters more than we think.

And yes-I’ll take the generic.

Because I trust the math.

And I trust the people who made it work.

Jamie Hooper

January 25, 2026 AT 19:15so like… if the generic hits harder or slower but the total is the same, its cool right?

nah i know its not but like… why do we even care about the peak??

just let me feel better 😅

Husain Atther

January 26, 2026 AT 04:58The 80%-125% range is a brilliant compromise. Not perfect, but practical.

It acknowledges biological variability while ensuring safety.

It’s not about identicality-it’s about therapeutic equivalence.

That’s the essence of modern pharmacology.

And yes, the science holds up.

When regulators demand both Cmax and AUC, they’re not being bureaucratic-they’re being responsible.

Every patient deserves this level of rigor.

Thank you for explaining it so clearly.

Helen Leite

January 27, 2026 AT 12:53WAIT… so Big Pharma is just letting generics in because they ‘met the numbers’??

WHAT IF THEY’RE LYING ABOUT THE SAMPLING??

WHAT IF THE LABS ARE CORRUPT??

WHAT IF THE 80-125% IS A TRAP TO LET POISON IN??

I’ve heard of people getting seizures after switching!!

THEY KNOW!! THEY ALL KNOW!! 😱

Izzy Hadala

January 27, 2026 AT 23:15It is worth noting that the log-normal distribution assumption underpinning the 80%-125% bioequivalence criterion is empirically validated across multiple drug classes and populations. The symmetric logarithmic interval ensures that both under- and over-exposure are equally weighted in statistical inference. Furthermore, the use of partial AUC for modified-release formulations, as suggested in the FDA’s 2023 draft guidance, represents a necessary evolution to accommodate complex pharmacokinetic profiles. The continued reliance on Cmax and AUC as primary endpoints is not an artifact of tradition, but a consequence of their robust correlation with clinical outcomes across decades of post-marketing surveillance.

Marlon Mentolaroc

January 29, 2026 AT 20:07Let’s be real-90% of generics pass because the manufacturers tweak the filler until the numbers work.

It’s not magic, it’s math hacking.

And yeah, it’s legal.

But don’t tell me your ‘generic’ Adderall isn’t just a sugar pill with a fancy coating.

I’ve been there. I’ve felt it.

And no, I’m not crazy.

Just… tired of being the lab rat.

Gina Beard

January 31, 2026 AT 08:19It’s not about the pill.

It’s about the trust.

And trust is fragile.

Don Foster

February 2, 2026 AT 00:14Cmax and AUC? Please everyone knows the real metric is how much the generic costs the insurance company

Who cares if the peak is 10% off as long as the pharmacy makes 20% more

And don't get me started on the FDA they're just corporate shills

Also why are you even reading this post you probably don't even know what LC MS MS is

LOL

siva lingam

February 3, 2026 AT 21:07so you spent 1000 words to say generics have to be close enough

cool

next

Shanta Blank

February 5, 2026 AT 09:53They don’t tell you this but… the same lab that tests the brand? Sometimes tests the generic too.

And the same analyst? Who’s been there since 2008?

And the same machine? That’s been calibrated with the same reference standard?

So… is it really a ‘generic’?

Or is it just a rebranded version of the same damn thing?

And who’s really benefiting?

Not you.

Not me.

Someone in a corner office with a gold-plated pen.

Chloe Hadland

February 6, 2026 AT 17:59I switched to a generic last year and my anxiety didn’t flare up.

That’s all I needed to know.

Thank you for explaining the science behind it.

It makes me feel safer knowing there’s real rigor behind it.

And honestly? I’m glad I saved $40 this month.

Small wins matter.

Amelia Williams

February 8, 2026 AT 11:24This is the kind of post that makes me love the internet.

You took something so technical and made it feel human.

And honestly? I’m proud of the people who do this work.

Not the CEOs.

Not the lawyers.

The scientists in the lab, at 3 a.m., taking blood samples, running LC-MS/MS, double-checking every decimal.

They’re the quiet ones who keep us alive.

So thank you.

And to everyone who takes a generic? You’re not taking a shortcut.

You’re part of the solution.