Geriatric Polypharmacy Impact Calculator

Calculate Impact of Medication Reviews

Estimate cost savings and adverse event reduction for your patient population using evidence-based geriatric polypharmacy interventions.

Intervention Details

Estimated Results

Enter patient count and review type to see results

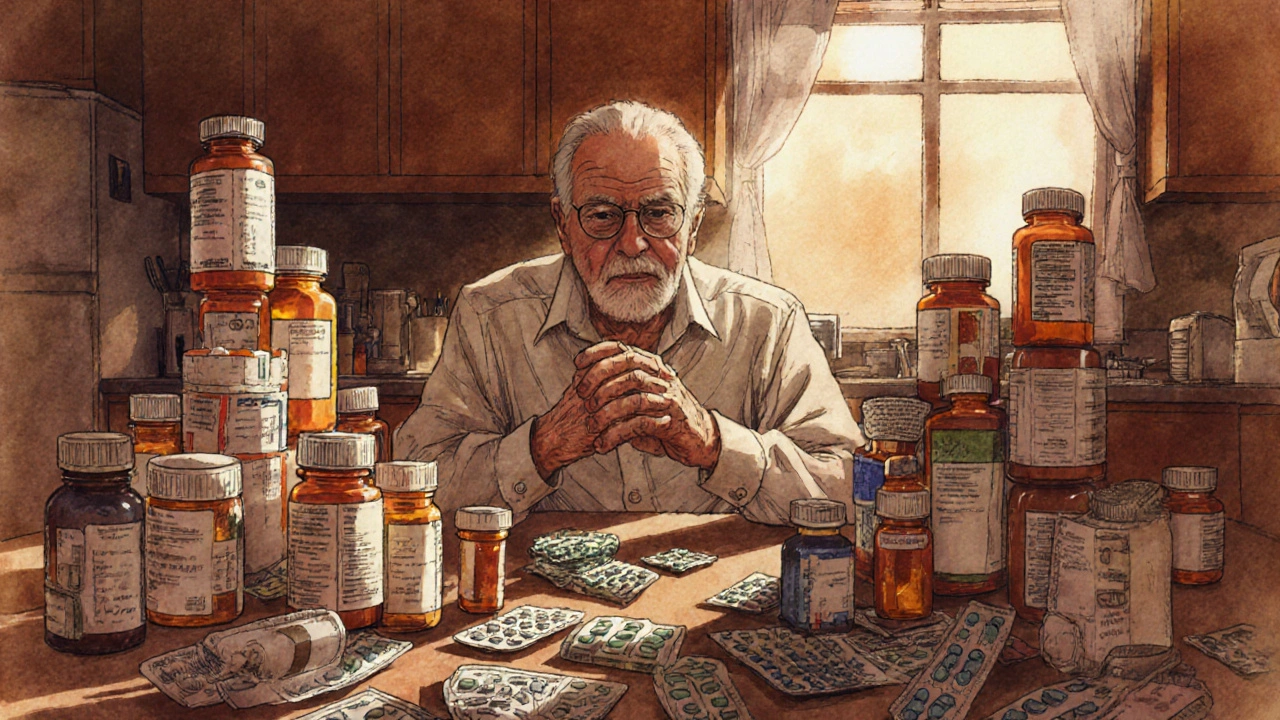

Geriatric polypharmacy is a condition where older adults regularly take five or more prescription drugs. It affects roughly 41 % of U.S. adults over 65 and drives a large share of medication‑related hospitalizations. The good news is that targeted interventions-especially full medication reviews-can dramatically lower the risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) and even save money.

Why Polypharmacy Is a Red Flag in Older Adults

When a patient’s medication list grows, two problems snowball:

- Each drug adds a new chance for drug‑drug interactions, dosing errors, or side‑effects.

- The cumulative burden often leads to poor adherence, confusion, and falls.

Data from the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (2018) show that taking more than four meds lifts the odds of an injurious fall by 30‑50 %. Every additional medication adds another 8 % risk, regardless of class. That’s why clinicians treat polypharmacy as a modifiable risk factor, not an inevitable part of aging.

Classification of Medication Review Interventions

Researchers split comprehensive medication reviews (CMRs) into three tiers. The table below lays out what each tier includes, how long it typically takes, and the impact on readmissions.

| Type | Components | Typical Duration | Effect on Unplanned Readmission | Cost Savings per Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Prescription list review only | 15‑20 min | No statistically significant change | ≈ $500 |

| Type II | List review + adherence assessment | 30‑35 min | ~5 % reduction (NS) | ≈ $1,050 |

| Type III | Full review, adherence, and face‑to‑face (or video) patient interview | 45‑60 min | 18.3 % reduction (95 % CI 12.7‑23.9 %) | ≈ $1,872 |

Core Clinical Tools for Deprescribing

Four evidence‑based tools dominate the deprescribing landscape. Their first definitions include microdata so search engines can map them correctly.

Beers Criteria is a list of potentially inappropriate medications for adults 65+ published by the American Geriatrics Society. The 2023 update adds new warnings for anticholinergics and certain antihypertensives.

STOPP/START criteria (Version 3, 2021) flags drugs that should be stopped (STOPP) and highlights therapies that are often omitted but indicated (START). Randomized trials show it improves clinical endpoints, especially when used by pharmacists.

FORTA list (Fit fOR The Aged) grades drugs from A (safe) to D (high risk) for older patients. European studies link FORTA‑guided reviews to fewer ADEs.

Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) scores each prescription on ten items such as indication, dosage, and drug‑drug interactions. Primary‑care teams using MAI report a 31 % drop in inappropriate prescribing.

Step‑by‑Step Workflow for a Successful Intervention

- Medication Reconciliation - Pull the full list from pharmacy records, home‑care reports, and patient self‑report. Studies cite an average of 22.7 minutes for a thorough reconciliation.

- Apply a Clinical Tool - Run the list through STOPP/START or FORTA. Expect 15‑20 minutes of decision‑support time per patient.

- Clinical Pharmacist Review - A pharmacist (often under a Collaborative Practice Agreement) evaluates each flagged item, checks for therapeutic duplication, and drafts deprescribing recommendations.

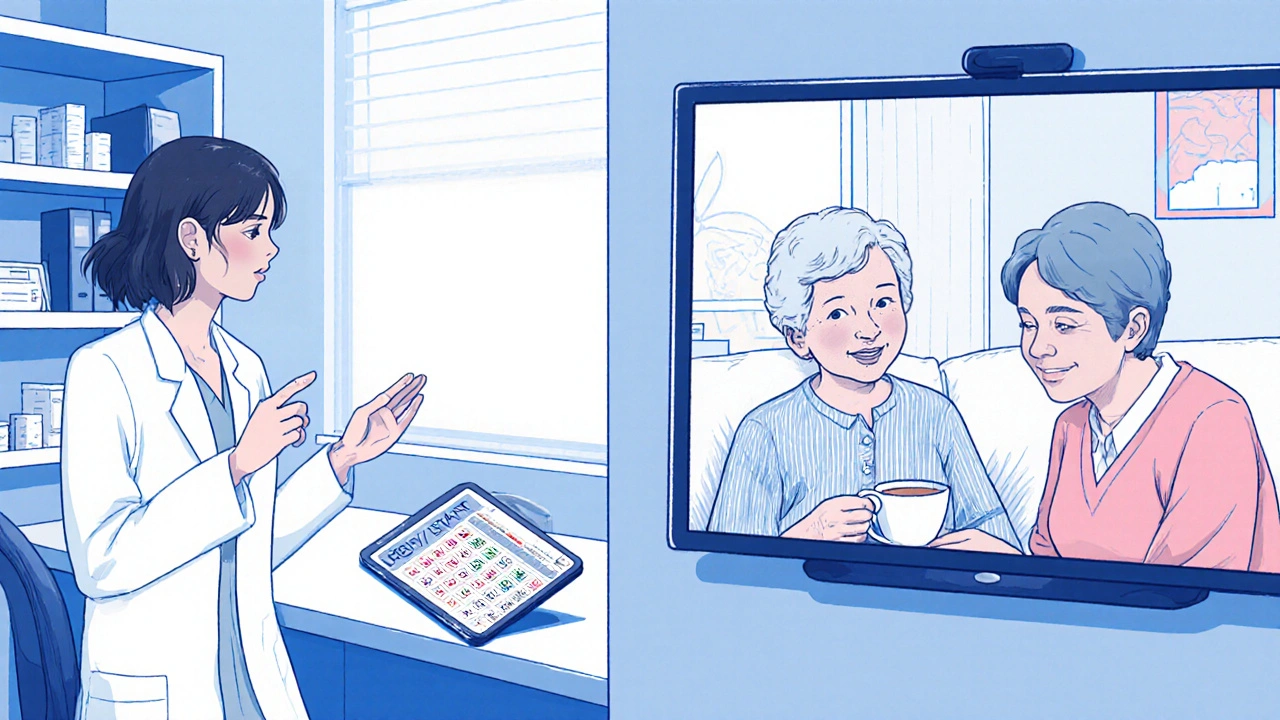

- Patient Consultation - Conduct a Type III CMR via video or in‑person. Discuss goals of care, address fears (68 % of seniors worry about stopping meds), and agree on a tapering schedule when needed.

- Implementation & Monitoring - Update the electronic health record (EHR), set alerts for follow‑up labs, and schedule a safety check within 30 days.

When teams follow this flow, they achieve roughly 22 % higher appropriate deprescribing rates than using medication count alone.

Economic Impact and Return on Investment

Comprehensive medication management saves money. A 2021 analysis (McFarland et al.) estimates $1,872 less spending per patient each year, mostly from avoided hospital stays. Put another way, every 100 patients enrolled saves nearly $187,000.

However, the upfront cost is clinical‑pharmacist time: 45‑60 minutes per Type III review translates to about $80‑$110 in labor per patient (based on median pharmacist hourly wages). When you factor in the $1,872 saved, the return on investment exceeds 2,000 % within a year.

Barriers and How to Overcome Them

Even with clear benefits, many practices stumble.

- Fragmented Care - Over 78 % of older adults see five or more providers annually. Solution: centralize medication data in the EHR and assign a dedicated pharmacist to reconcile across specialties.

- Time Constraints - Primary‑care physicians often have <5 minutes per patient for medication checks. Solution: embed pharmacy technicians to collect histories, freeing pharmacists for the in‑depth review.

- Reimbursement Gaps - Only 15 % of Medicare Advantage plans pay specifically for CMRs. Solution: bill under Chronic Care Management codes or seek value‑based contracts that reward reduced readmissions.

- Regulatory Limits - Collaborative Practice Agreements (CPAs) are unavailable in 28 % of states. Solution: work within telehealth‑enabled pharmacist‑led programs that partner with physicians for protocol‑driven deprescribing.

- Patient Resistance - 68.4 % of seniors fear stopping meds. Solution: use shared decision‑making scripts, show evidence of safety, and start with low‑risk drugs.

Future Directions: AI and Personalized Risk Scores

Artificial intelligence is already entering the field. Epic’s “Polypharmacy Risk Score” (released April 2024) predicts ADEs with 87.3 % accuracy by combing medication lists, lab values, and comorbidities. Clinics that integrate the score into their CMR workflow see a 9 % jump in appropriate deprescribing.

Looking ahead, the upcoming 2026 Beers Criteria will embed deprescribing algorithms directly into EHR order sets, making it almost impossible to prescribe high‑risk drugs without a justification prompt.

Key Takeaways for Clinicians and Administrators

- Identify patients on ≥5 meds early; they are at higher risk for falls and ADEs.

- Prioritize Type III CMRs - the only model proven to cut readmissions.

- Use STOPP/START or FORTA as the decision‑support backbone.

- Secure a clinical‑pharmacist with a CPA whenever possible.

- Track cost savings and safety outcomes to justify program expansion.

What defines geriatric polypharmacy?

Geriatric polypharmacy generally means a patient aged 65 or older regularly takes five or more prescription medications. The threshold comes from the American Geriatrics Society and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

How does a Type III comprehensive medication review differ from Types I and II?

Type III adds a direct patient interview (in‑person or video) to the medication list review and adherence assessment. This face‑to‑face element allows clinicians to align therapy with patient goals, leading to an 18 % drop in unplanned readmissions, a benefit not seen with the lighter Type I or II reviews.

Which clinical tool is most effective for deprescribing?

Evidence from European Geriatric Medicine shows STOPP/START and FORTA generate the biggest reductions in ADEs. STOPP/START flags both drugs to stop and therapies to start, while FORTA grades drug safety, making them complementary.

What are the main cost savings from a pharmacist‑led polypharmacy program?

A typical program saves about $1,800 per patient annually by cutting hospitalizations and emergency‑department visits. Even after accounting for pharmacist time, the net ROI exceeds 2,000 % within the first year.

How can clinics overcome the lack of CPA authority in some states?

When CPAs aren’t available, the safest route is to use protocol‑driven deprescribing under physician oversight, or partner with telehealth pharmacist services that operate under a supervising physician’s license.

Abhinav B.

October 24, 2025 AT 21:18Look, polypharmacy is a massive issue and we need to act now. A solid medication review can cut down adverse events dramatically, and the data backs it up. The numbers in the post show a clear ROI, so clinics should adopt Type III reviews ASAP. Stop waiting for patients to get hurt before you intervene.

Sarah Keller

October 25, 2025 AT 01:28When we consider the ethical dimension of prescribing, we must ask whether we're honoring the autonomy of elders or just adding pills for profit. A thorough STOPP/START assessment respects their lived experience while reducing harm. The philosophical basis for deprescribing lies in the principle of non‑maleficence, so let’s keep that front‑and‑center.

Veronica Appleton

October 25, 2025 AT 05:38Totally agree with the need for comprehensive reviews the tools mentioned like Beers and FORTA are essential they give a clear framework for clinicians to follow

the sagar

October 25, 2025 AT 09:48All these pharma giants are just lining their pockets.

Grace Silver

October 25, 2025 AT 13:58The point about fragmented care hits home patients see too many docs and the med list gets out of control A centralized pharmacist can be the glue that holds it together

Clinton Papenfus

October 25, 2025 AT 18:08Esteemed colleagues the evidence presented underscores the fiscal prudence of implementing Type III medication reviews; the projected savings per patient are compelling and merit serious consideration.

Zaria Williams

October 25, 2025 AT 22:18Honestly this whole thing sounds like a fad but the stats dont lie they are real and we need to stop overprescribin we cant just keep throwing pills at older folks lol

ram kumar

October 26, 2025 AT 02:28Behold the tragedy of our times: a generation drowning in a sea of tablets, each pill a tiny whisper of corporate greed, each prescription a brick in the wall of iatrogenic doom. We march forward with good intentions, yet the very tools meant to heal become shackles upon the frail. The data is stark-each additional medication nudges the odds of a fall upward by eight percent, a silent assassin in the night. Imagine the elderly, bewildered by a litany of names, their memories tangled with dosage schedules, their confidence eroded with every new warning label. The cost is not merely financial; it is the loss of dignity, the erosion of autonomy, the quiet surrender to a system that values profit over personhood. Yet amidst this gloom, a beacon shines: comprehensive medication reviews, especially the Type III model, promise a reversal of this tide. A diligent pharmacist, armed with STOPP/START or FORTA, can peel back the layers of unnecessary therapy, exposing the patient’s true needs. The ROI figures-nearly two thousand percent-are not just numbers; they are lives reclaimed, hospital beds spared, families spared the heartache of preventable readmissions. We must champion these interventions, embed them into the fabric of primary care, and demand that health systems allocate the resources necessary for their execution. Let us not be passive witnesses to this crisis; let us be the architects of a future where medication is a bridge, not a barrier, to healthy aging.

Melanie Vargas

October 26, 2025 AT 05:38Love the energy here! 😊 Implementing these reviews could really change the game for seniors. 👍

Deborah Galloway

October 26, 2025 AT 09:48Thank you for sharing all this helpful information. It’s reassuring to see evidence-based approaches that truly benefit older adults.

Benjamin Sequeira benavente

October 26, 2025 AT 13:58Let’s push this forward! Clinics need to schedule those Type III reviews now-no more delays!