When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same effect as the brand-name version. But what if your body reacts differently-not because the drug is weaker, but because of your genes? For many people, the difference between a drug working perfectly or causing serious side effects comes down to something invisible: your DNA. And it’s not just you-it’s often your family too.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than You Think

Generic drugs are chemically identical to their brand-name counterparts. That’s a fact. But identical doesn’t mean identical in how your body handles them. Your genes control how quickly your liver breaks down drugs, how well your cells absorb them, and even how your body reacts to them. This field is called pharmacogenetics, and it’s not science fiction-it’s already changing how doctors prescribe medications.Take CYP2D6, a gene that affects how your body processes about 25% of all prescription drugs. If you have certain variants of this gene, you might be a slow metabolizer. That means drugs like paroxetine, codeine, or sertraline build up in your blood, raising your risk of side effects. On the flip side, if you’re a fast metabolizer, the drug gets broken down too quickly, leaving you with no relief. This isn’t rare. Up to 10% of Europeans and 30% of East Asians carry variants that make them poor or ultra-rapid metabolizers of CYP2D6-dependent drugs.

And it’s not just CYP2D6. The CYP2C9 gene affects warfarin, a blood thinner. People with two copies of the *2 or *3 variant need up to 30% less warfarin than average. If they don’t get that adjusted dose, they’re at high risk for dangerous bleeding. Similarly, the TPMT gene determines how your body handles thiopurines used in cancer and autoimmune treatments. Patients with low TPMT activity can develop life-threatening drops in white blood cells if given standard doses. Testing for these variants before prescribing isn’t optional anymore-it’s standard care in many hospitals.

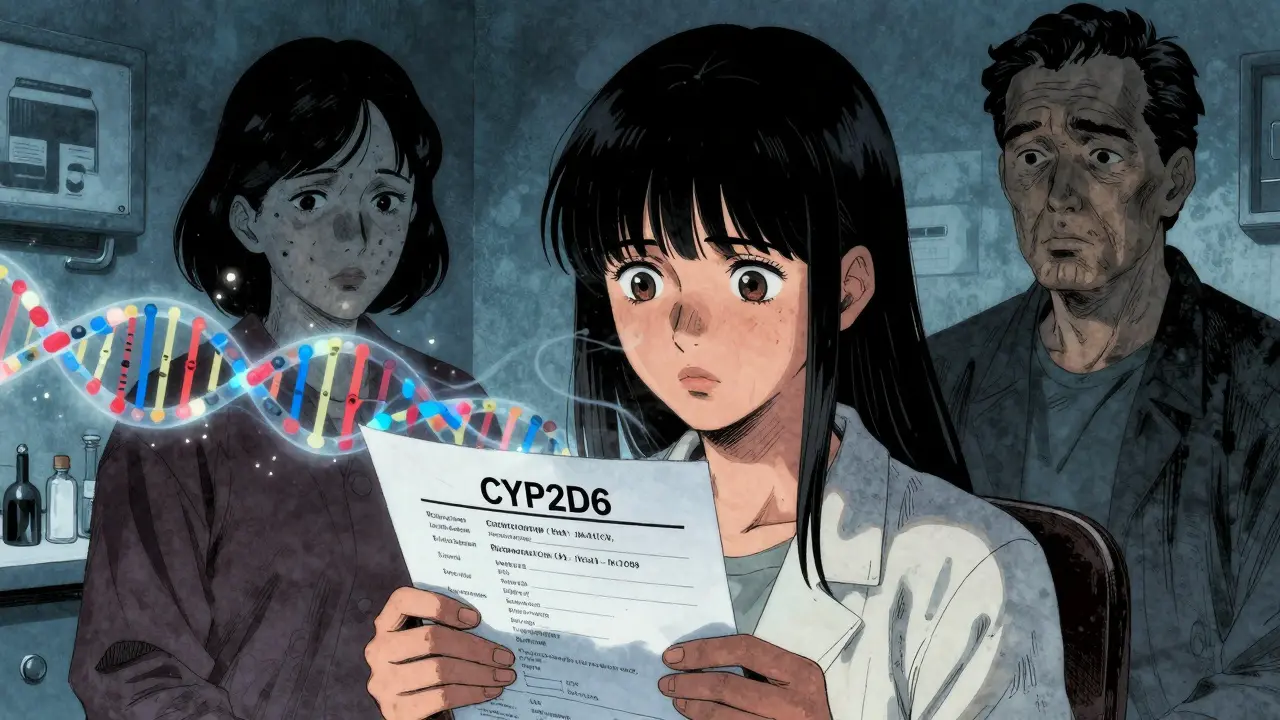

Family History Isn’t Just About Diseases-It’s About Drugs

You’ve probably heard, “Your mom had a bad reaction to aspirin.” That’s not just a family story-it’s a genetic clue. If your parent or sibling had a severe side effect from a medication, chances are you carry the same genetic variant. Studies show that family history is one of the strongest predictors of how you’ll respond to a drug, even before any genetic test is done.For example, if your father had to stop taking clopidogrel (a common heart drug) because it didn’t work, he likely has a variant in the CYP2C19 gene that makes him a poor metabolizer. You might have inherited that same variant. If you’re prescribed clopidogrel next, you could be at risk of a heart attack because the drug never activates in your body. Knowing your family’s history could save your life.

But here’s the catch: most doctors don’t ask. A 2022 survey of over 1,200 clinicians found that while 68% felt confident interpreting CYP2D6 results, only 32% felt comfortable with HLA-B*15:02, a gene linked to severe skin reactions from carbamazepine. And 79% said they didn’t have time to review genetic data during appointments. That means even if you know your family history, your doctor might not connect the dots.

Population Differences Are Real-and Important

Genetic variants aren’t spread evenly across the world. A 2024 study comparing Tunisian and Italian populations found that certain gene variants affecting statin and metformin response varied dramatically. In Sub-Saharan African populations, the rs3846662 variant in the HMGCR gene (linked to reduced pravastatin effectiveness) was far more common than in Europeans. In Asia, 15-20% of people are poor metabolizers of proton pump inhibitors due to CYP2C19 variants-compared to just 2-5% of Caucasians.This matters because many drug dosing guidelines were developed using data from mostly white populations. If you’re of African, Asian, or Indigenous descent, standard doses might be too high-or too low-for you. Warfarin dosing used to be based on weight and age, but now we know African Americans typically need higher doses than Europeans because of differences in CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes. Genotype-guided dosing improved time in the therapeutic range by 7-10% in clinical trials. That’s not a small gain-it’s the difference between a stroke and a healthy life.

Real Stories: When Genetics Saved a Life-or Almost Didn’t

One patient in Manchester shared their story on a local health forum: “My mom died from a reaction to 5-fluorouracil during chemotherapy. I was diagnosed with colon cancer last year. I insisted on a DPYD test before treatment. The results showed I had the same dangerous variant. My oncologist cut my dose by 33%. I finished chemo with only mild nausea. No hospitalizations.”But not everyone is so lucky. A Reddit user from Leeds wrote: “I paid $350 for a GeneSight test. It said I was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. My psychiatrist ignored it and prescribed sertraline. Two weeks later, I had serotonin syndrome. I ended up in the ER. No one listened.”

These aren’t outliers. A 2023 Mayo Clinic study of 10,000 patients who got preemptive genetic testing found that 42% had at least one high-risk gene-drug interaction. Of those, 67% had their meds changed-and adverse events dropped by 34%. That’s not luck. That’s science.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for your doctor to bring this up. Here’s how to take control:- Ask about your family’s drug history. Not just “did they have allergies?” but “did any of them have bad reactions to antidepressants, painkillers, or blood thinners?”

- Request pharmacogenetic testing if you’re starting a new medication with known genetic links-like SSRIs, warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain cancer drugs. Tests like Color Genomics and OneOme cost under $250 and cover 10-15 key genes.

- Bring your results to your pharmacist. Pharmacists are trained to interpret these reports. They can flag dangerous interactions your doctor might miss.

- Push for EHR integration. Ask if your clinic uses Epic or another system with built-in CPIC alerts. If not, advocate for it.

The NHS has started piloting preemptive pharmacogenetic testing in several regions. In the U.S., over 167,000 patients at Vanderbilt and Mayo Clinic have already been tested. This isn’t the future-it’s happening now.

The Road Ahead

The global pharmacogenomics market is projected to hit $25 billion by 2030. More than 300 drug labels now include genetic information from the FDA. And in 2023, the FDA approved the first antidepressant selection tool based on genetic testing. But the biggest barrier isn’t science-it’s access.While 89% of academic hospitals offer testing, only 32% of community hospitals do. If you’re in a rural area or rely on public healthcare, you might still be stuck with trial-and-error prescribing. That’s why knowing your own genetic risks-and your family’s-is more important than ever.

Switching to a generic drug shouldn’t mean guessing whether it’ll work. Your genes already know. The question is: will anyone listen?

Can family history really predict how I’ll respond to generic drugs?

Yes. If close relatives had severe side effects or no effect from a medication, you likely share the same genetic variants. For example, if your parent had a dangerous reaction to codeine or clopidogrel, you could be at similar risk. Family history is one of the strongest early indicators of how your body will handle a drug-even before genetic testing.

Are generic drugs less effective because of genetics?

No. Generic drugs are chemically identical to brand-name versions. The issue isn’t the drug-it’s how your body processes it. Your genes determine whether you break down the drug too fast (making it ineffective) or too slow (causing toxicity). This applies to both generics and brand-name drugs equally.

Which drugs are most affected by genetic differences?

The most well-studied include warfarin (CYP2C9, VKORC1), clopidogrel (CYP2C19), SSRIs like sertraline and paroxetine (CYP2D6), thiopurines like azathioprine (TPMT), and chemotherapy drugs like 5-fluorouracil (DPYD). Over 300 drug labels now include genetic guidance from the FDA.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance in the UK?

Currently, the NHS does not routinely cover pharmacogenetic testing outside of specific cases like TPMT testing before thiopurine therapy. However, pilot programs are underway in several regions. Private tests from companies like Color Genomics and OneOme cost around £200-£400 and are often paid out-of-pocket. Some private insurers may cover it if prescribed by a specialist.

Can I get tested before I’m prescribed a drug?

Yes. Preemptive testing-where you get tested once and the results are stored in your medical record for future use-is becoming more common. Programs like Vanderbilt’s PREDICT and Mayo Clinic’s RIGHT Protocol have tested over 160,000 patients this way. If you’re planning long-term medication use (e.g., for depression, heart disease, or chronic pain), preemptive testing can prevent dangerous mistakes down the line.

If you’re starting a new medication and have a family history of bad reactions, don’t wait. Ask your doctor about genetic testing. It might be the difference between healing and harm.

John Watts

February 10, 2026 AT 05:28Yo, this post hit different. I never thought about how my grandma’s bad reaction to codeine was actually a genetic red flag. My doc just shrugged when I mentioned it-until I brought up CYP2D6. Now they’re testing me before any new med. If you’ve got family drama with meds? Don’t wait. Get tested. It’s not paranoia-it’s prevention. 🙌

Chima Ifeanyi

February 11, 2026 AT 17:30While the pharmacogenetic framework is theoretically sound, the operationalization of CYP450 phenotyping remains plagued by epistemic reductionism. The assumption that single-nucleotide polymorphisms dictate pharmacokinetic outcomes ignores pleiotropy, gene-environment interactions, and microbiome-mediated metabolism. Your ‘genetic destiny’ narrative is dangerously deterministic.

Tori Thenazi

February 11, 2026 AT 22:45Okay but… have you seen what’s in generics?? I read somewhere that the fillers are made in China and sometimes they add… I don’t know… *something*… to make you dependent?? Like, what if it’s not your genes?? What if it’s the *filler*?? And what if Big Pharma is hiding this?? I’ve got a cousin who got sick after a generic and now she won’t touch anything without a brand label… I think they’re tracking us through our prescriptions… 😳

Elan Ricarte

February 12, 2026 AT 08:36Let me get this straight-you’re telling me my entire life of ‘I just can’t handle antidepressants’ was just my DNA being a stubborn bastard? I spent 7 years on 12 different SSRIs thinking I was broken. Turns out I’m just a CYP2D6 slow-mo mess with a side of bad luck. Now I’m mad. Not at the doc. Not at the meds. At the system that didn’t test me before I nearly killed myself trying to ‘just push through.’

And don’t even get me started on how insurance won’t cover testing unless you’re already in the ER. Like, hello? Prevention is cheaper than trauma. But nah. We’d rather pay for ambulance rides than $200 tests. Fuck this.

Ritteka Goyal

February 14, 2026 AT 07:58India is leading the world in generic drug production and yet we are the ones suffering the most from side effects? How ironic? My aunt took a generic blood thinner and almost died-her doctor said ‘it’s the same chemical’ but she had the CYP2C9 variant and no one tested her! We have 1.4 billion people and still no national pharmacogenomics program? Shame! Why can’t we be like the US or UK? We are smart people-we can do this! I have already ordered a Color Genomics kit and will share my results with my entire village. Genetic awareness is the next revolution!

P.S. I typed this on my phone so sorry for typos 😊

Monica Warnick

February 14, 2026 AT 16:51My mom took warfarin for 12 years. I took it for 3 weeks. She had zero issues. I almost bled out. They tested me after. Turned out I’m a VKORC1 variant. My mom never got tested. She just got lucky. I think… I think maybe I’m just… unlucky? Or maybe it’s not luck. Maybe it’s just… biology. I don’t know. I’m tired.

Ashlyn Ellison

February 16, 2026 AT 09:50My cousin got tested after a bad reaction to a generic statin. Turns out she’s a poor metabolizer for HMGCR. They changed her dose. She’s fine now. I got tested too. Same variant. I’m on a different statin. No side effects. Simple. Why isn’t this standard? Why does it take a near-death experience to get a test? Just test everyone. It’s not that hard.

Jonah Mann

February 17, 2026 AT 00:35So I got my GeneSight results last year. CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Told my psych. She said ‘oh cool’ and gave me the same med. I had to go to a pharmacist to get them to listen. Pharmacist pulled up the CPIC guidelines on her screen and said ‘if you prescribe this, you’re risking serotonin syndrome.’ She changed it. Next day I felt like a new person. My point? Don’t trust your doc unless they’ve heard of CPIC. Ask for the pharmacist. They’re the real heroes.

p.s. I spelled ‘pharmacist’ wrong in my first draft. Sorry.

THANGAVEL PARASAKTHI

February 18, 2026 AT 02:08As a medical student from India, I find this topic so important. In rural areas, people take generics because they have no choice. No one asks about family history. No one tests. But I’ve seen cases-three patients in my rotation alone-where a simple gene test would’ve saved them. We need community health workers trained to ask: ‘Did your parent have a bad reaction to medicine?’ Just that one question. It changes everything. I’m starting a project at my college to train students to do this. Small steps.

Chelsea Deflyss

February 19, 2026 AT 12:30Wow. Just wow. I can’t believe people are still taking generic drugs without genetic testing. It’s like driving a car without a seatbelt and saying ‘I’m fine.’ You’re not fine. You’re just lucky. And now you’re telling everyone else to be reckless? I’m not judging… but I am disappointed.

Tricia O'Sullivan

February 20, 2026 AT 14:12Thank you for this meticulously researched and profoundly important contribution. The clinical implications of pharmacogenetics are not merely academic-they are existential. I am particularly moved by the anecdote regarding the Manchester patient and their DPYD variant. Such narratives underscore the urgent necessity for equitable access to genomic medicine. I shall be forwarding this to my hospital’s ethics committee with a view toward policy reform.

Scott Conner

February 20, 2026 AT 18:18Wait so if my grandpa had a bad reaction to aspirin, does that mean I should avoid all NSAIDs? Or just the ones metabolized by CYP2C9? I’m confused. Is there a chart? I wanna know before I take Advil for my headache.

Randy Harkins

February 22, 2026 AT 13:04Thank you for writing this. 💙 I’ve been through the ‘med carousel’-10 antidepressants, 3 anxiety meds, 2 painkillers that made me feel like I was being eaten alive from the inside. Then I got tested. CYP2D6 ultra-rapid. That’s why nothing worked. Now I’m on a drug that actually fits me. I’m sleeping. I’m not crying all day. I’m not scared to leave the house. This isn’t science. This is survival. And it’s available. Ask. Test. Advocate. You deserve to feel okay.

Angie Datuin

February 24, 2026 AT 00:14I’m a nurse. We just started offering pharmacogenetic testing in our clinic last month. We had one patient who refused because ‘it’s too expensive.’ I paid for her test out of my pocket. She’s on her third med now and actually sleeping. She cried when she told me. I cried too. This is why I do this job.