When you pick up a prescription for generic lisinopril or metformin, you might assume the price is set by the market - low because lots of companies make it. But that’s not the whole story. The truth is, government control of generic prices shapes what you pay at the pharmacy more than you realize. It’s not about setting a fixed price like in Europe. It’s a web of rebates, programs, and rules that quietly keep costs down - or sometimes, let them spike.

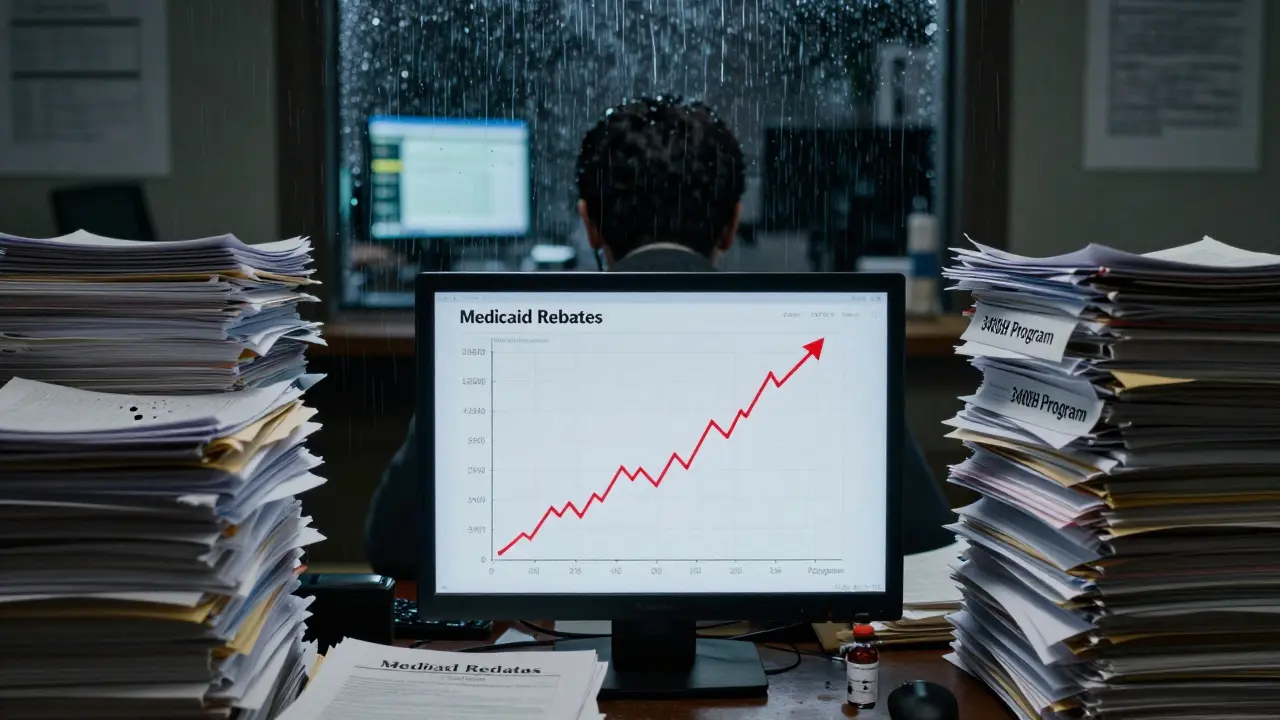

How Medicaid Keeps Generic Drugs Affordable

The biggest force holding down generic drug prices isn’t competition alone - it’s Medicaid. Since 1990, the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program has forced drugmakers to give the government a cut of every generic sold. For generics, that’s the bigger of two numbers: either 23.1% of the average price manufacturers charge wholesalers, or the difference between that price and the lowest price they give any other buyer. In 2024, this program brought in $14.3 billion in rebates - 78% of all Medicaid drug rebates. That money doesn’t go to patients directly, but it lowers the overall cost of drugs, which helps keep premiums and copays lower for everyone.

These rebates aren’t optional. If a company doesn’t report accurate prices to CMS every quarter, they lose their right to sell to Medicaid. That’s a huge penalty - Medicaid covers nearly 80 million Americans. So manufacturers play by the rules, even if it means shrinking their margins.

Medicare Part D and the Out-of-Pocket Cap

If you’re on Medicare, your generic drug costs changed dramatically in 2025. Before, you paid 25% coinsurance during the initial coverage phase, and once you hit $8,000 in out-of-pocket spending, you got catastrophic coverage. Now, thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act, your maximum out-of-pocket cost for all drugs - brand or generic - is capped at $2,000 a year. That’s huge for people taking five or six generics daily.

For low-income Medicare beneficiaries (LIS), the impact is even bigger. They pay between $0 and $4.90 per generic prescription. Compare that to brand-name drugs, where they pay up to $12.15. That’s not because generics are cheaper to make - it’s because the government designed the system to protect the most vulnerable.

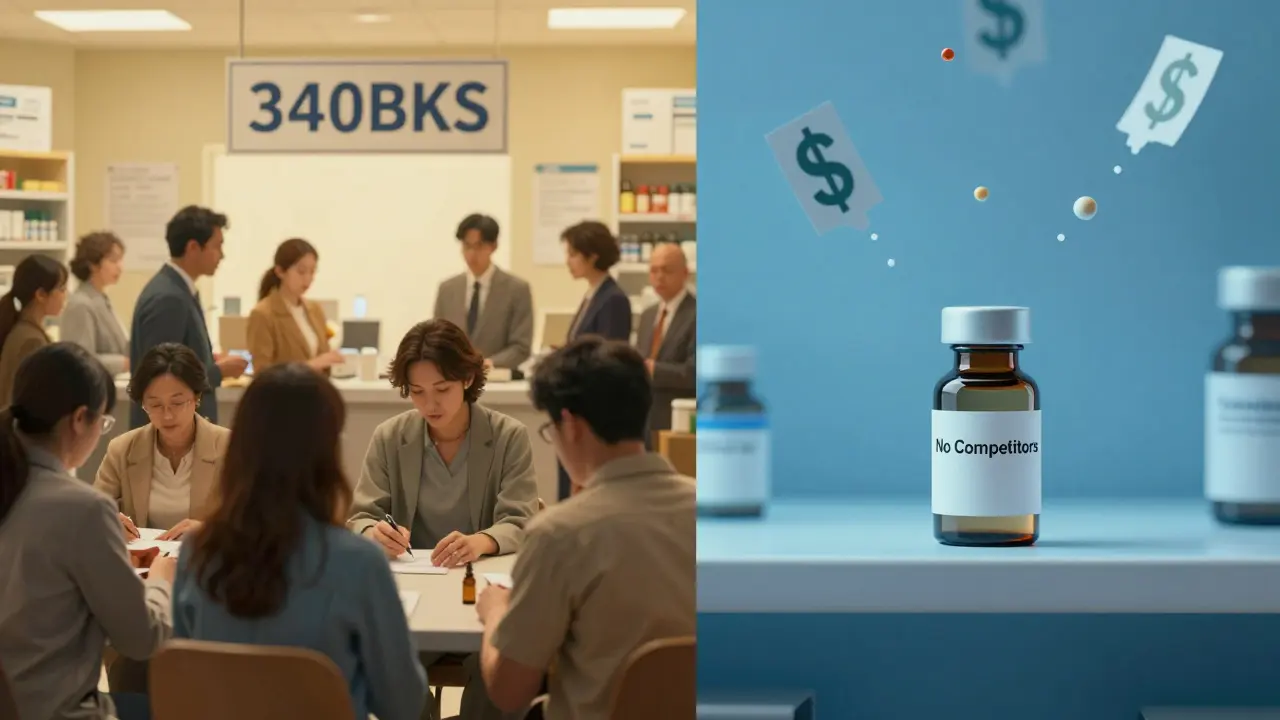

The 340B Program: Cheap Drugs for the Poorest Patients

While Medicaid helps the state, the 340B Drug Pricing Program helps safety-net clinics and hospitals. It forces drugmakers to sell outpatient drugs - including generics - at steep discounts to places that serve low-income, uninsured, or rural patients. Discounts range from 20% to 50% below the average market price. Community health centers report that 87% of patients stick to their meds better because they can actually afford them.

But here’s the catch: 340B doesn’t lower prices for everyone. Only qualifying clinics can use it. If you’re not treated at one of these places, you won’t see the discount. And PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers) sometimes fight these discounts, arguing they distort pricing. But for the patients who rely on them, it’s life-changing.

Why Generic Prices Still Jump - Even With All These Rules

Here’s the dark side: when only one or two companies make a generic drug, prices can explode. Take pyrimethamine (Daraprim). In 2024, when only two manufacturers were left, the price jumped 300%. No one was competing. No one was forcing rebates. The government didn’t step in because it doesn’t control prices directly - only through indirect tools.

That’s the flaw in the U.S. system. We trust competition to keep prices low. But when competition disappears - because manufacturers quit making low-margin drugs, or because they can’t get raw materials - prices go haywire. The FDA approved 1,247 generics in 2024, but many are for common drugs with dozens of makers. For obscure, older drugs? Fewer than five companies bother. That’s where the system breaks.

What You Really Pay - And Why It’s So Confusing

You might think your insurance covers your generic drug. But here’s what happens behind the scenes: your pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) negotiates a price with the manufacturer, gets a rebate, and then charges you a copay. The rebate? Often never reaches you. A 2025 Senate report found 68% of generic drug rebates are kept by PBMs or used to lower premiums for other customers - not you.

That’s why Mary Johnson, a 68-year-old in Florida, got hit with a $90 bill for her generic lisinopril. Her plan switched to a different generic maker with a higher copay tier. She didn’t know. Her pharmacist didn’t warn her. Her insurance statement didn’t explain it. That’s the reality: prices change without notice. You’re not getting the best deal - you’re getting whatever your plan’s PBM decided was profitable.

On average, Medicare beneficiaries spend $327 a year on generics now - down from $412 in 2022. But 30% of Americans still struggle to afford meds. And 18% say generic costs are part of that burden. It’s not just about the sticker price. It’s about hidden shifts, confusing tiers, and opaque rebates.

How the U.S. Compares to the Rest of the World

Other countries don’t wait for competition to work. Canada, the UK, and Germany set prices directly. The UK’s NICE evaluates whether a drug is worth its cost. Germany uses a similar system. The result? U.S. generic prices are 1.3 times higher than the average of 32 other rich nations. But here’s the twist: we fill 90% of prescriptions with generics. Europe? Only 65%. We get more generics faster - but we pay more for them.

Why? Because we don’t have a single buyer. In the UK, the government buys for everyone. In the U.S., Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers, and employers all negotiate separately. That fragmentation means no one has enough power to push prices down hard - unless they’re the VA. The VA, which buys for veterans, gets 40-60% discounts by negotiating as one big buyer. Experts like Dr. Peter Bach say Medicare should do the same. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that could save $12.7 billion over ten years.

What’s Coming in 2026 and Beyond

The biggest change isn’t about controlling all generics - it’s about targeting the most expensive ones. Starting in 2026, Medicare will negotiate prices for 15 high-cost drugs. In 2027, that list includes generic versions of apixaban and rivaroxaban - blood thinners used by over 5 million Medicare patients. These aren’t new drugs. They’re generics. But they cost billions because they’re used so widely.

Industry analysts predict these negotiated prices could drop 25-35%. That’s huge. It’s the first time the government is directly cutting prices on generics - not through rebates, but through negotiation. It’s a quiet revolution.

But it’s not without pushback. Drugmakers are suing, claiming it’s an unfair seizure of property. Critics warn that squeezing margins too hard will make manufacturers quit making low-profit generics. The truth? Most generic makers already operate on under 15% profit. If prices fall too far, some will leave the market. That could lead to shortages - and then, price spikes.

What You Can Do Right Now

Don’t just accept whatever your pharmacy charges. Use the Medicare Plan Finder tool. It’s free. Compare plans every year. Look for ones with $0 copays on your generics. Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the lowest-cost generic version?” Sometimes, switching brands cuts your cost by half.

If you’re on Medicaid or qualify for LIS, make sure you’re enrolled. You’re entitled to $0-$4.90 copays. If your plan doesn’t cover your generic at $0, call your state’s SHIP (State Health Insurance Assistance Program). They helped 12.7 million people in 2024 with exactly this.

And if you’re paying over $50 a month for a generic you’ve taken for years - question it. Ask your doctor if there’s a cheaper alternative. Ask your pharmacy if they can get it through 340B if you’re eligible. You’re not powerless. The system is complex, but it’s not unbreakable.

Sue Latham

January 29, 2026 AT 12:15Oh honey, let me tell you - I used to think generics were just cheap knockoffs. Then I found out Medicaid’s rebate system is basically the government sneaking in like a financial ninja to keep prices down. And yet, I still got slapped with a $90 bill for lisinopril. Like… what even is this system? I’m paying for a drug that’s been around since the 70s. It’s not a luxury, it’s a lifeline. And yet here we are, playing pharmacy roulette.

And don’t get me started on PBMs. They’re the middlemen who act like they’re doing us a favor while quietly pocketing 68% of the rebates. I swear, if I had a dollar for every time I was told ‘this is the lowest cost option,’ I’d be able to pay for my meds outright.

It’s not about profit margins - it’s about power. And right now, the power’s in the hands of people who don’t care if you skip a dose because you can’t afford it.

But hey, at least we’ve got 90% generic usage. I guess that’s something. Maybe we should rename it ‘The Great American Generic Scam.’

James Dwyer

January 30, 2026 AT 08:43There’s real hope in the changes coming. The $2,000 out-of-pocket cap for Medicare Part D? That’s life-changing for people on multiple generics. And the fact that Medicare’s finally negotiating prices on high-use generics like apixaban? That’s the first real step toward fixing a broken system.

It’s not perfect, but it’s progress. People who’ve been paying $50 a month for blood thinners are going to breathe easier. That’s not policy - that’s humanity.

jonathan soba

January 31, 2026 AT 09:47Let’s be brutally honest: the U.S. system is a Rube Goldberg machine of regulatory arbitrage. Medicaid rebates, 340B discounts, PBM opacity - it’s all designed to look like a market-driven solution while actually being a patchwork of subsidies that benefit no one except the intermediaries.

And the 1.3x price premium over other OECD nations? That’s not innovation - that’s institutionalized rent-seeking. The fact that we produce more generics doesn’t make us efficient. It makes us gullible.

Meanwhile, Canada and Germany set prices based on clinical value. We set them based on who has the best lobbyist. The math is clear. The moral is not.

matthew martin

January 31, 2026 AT 12:25Man, this whole thing is like trying to navigate a maze blindfolded while someone keeps moving the walls.

One day you’re paying $4 for metformin because your pharmacy’s got a deal with a 340B clinic. Next week, your insurer switches PBMs and suddenly it’s $48 because ‘the new generic’ - which is literally the same chemical - is now in a higher tier.

I’ve had patients cry in my office because they’re choosing between insulin and rent. And the worst part? No one’s lying to them. The system just doesn’t care enough to make it simple.

But here’s the wild twist: if you dig deep enough, there are loopholes that actually work. SHIP counselors? Lifesavers. Medicare Plan Finder? Underrated. Asking your pharmacist, ‘Is there a cheaper version?’ - that’s your secret weapon.

It’s not fair. But it’s not hopeless. We just gotta stop waiting for the system to fix itself and start using the tools we already have.

And if you’re one of those people who says ‘just buy in bulk’ or ‘get it from Canada’ - yeah, that’s great. But not everyone can. Not everyone has the time, the access, or the privilege to be a drug-shopping ninja. We need systemic change, not hustle culture fixes.

Chris Urdilas

February 1, 2026 AT 02:44So let me get this straight - we’ve got a system that’s so complex, it takes a PhD to understand why your $0.10 pill costs $45, but we’re surprised when people skip doses?

Meanwhile, the VA gets 60% discounts because they buy for everyone. But Medicare? Can’t even negotiate until 2026. And even then, only 15 drugs.

It’s like the government’s playing Monopoly with real people’s lives. And we’re all just waiting for someone to say, ‘Oh, sorry, I didn’t realize you were actually trying to survive.’

Phil Davis

February 2, 2026 AT 19:33Everyone’s mad about PBMs. Fair. But let’s not forget - the manufacturers are the ones who stopped making pyrimethamine until they could jack up the price 300%. They knew exactly what they were doing.

It’s not just the middlemen. It’s the whole chain. And until we hold the makers accountable, not just the middlemen, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Irebami Soyinka

February 3, 2026 AT 01:42USA still thinks capitalism = freedom? LOL. You pay more for generics than Germany, but you call it ‘choice’? My people in Lagos pay less for metformin than your elderly. And we don’t have Medicaid.

You built a system where profit is sacred and people are disposable. And now you’re shocked when people die because they can’t afford a $5 pill?

Stop pretending this is about ‘market forces.’ This is about greed dressed up as policy. We see you.

✊🇳🇬

Katie Mccreary

February 4, 2026 AT 17:14My mom died because she skipped her lisinopril to afford groceries. This isn’t a policy debate. It’s a funeral.

And you’re all here talking about ‘rebates’ like it’s a spreadsheet problem. It’s not. It’s a moral collapse.

Kevin Kennett

February 5, 2026 AT 10:14Look - I get it. The system’s a mess. But if you’re paying over $50 a month for a generic you’ve been on for a decade, you’re not powerless. You just haven’t asked the right questions.

Go to your pharmacy. Ask: ‘Is this the lowest-cost generic?’ Ask your doctor: ‘Is there a cheaper alternative?’ Call SHIP. Use the Medicare Plan Finder.

One woman I know cut her monthly cost from $82 to $4.50 by switching brands and using a 340B clinic. She didn’t have a degree in pharmacy policy. She just didn’t accept the price.

Don’t wait for the government to fix this. Fight for your own script. You’ve got more power than you think.

Jess Bevis

February 5, 2026 AT 22:58340B clinics save lives. Period.

Rose Palmer

February 6, 2026 AT 14:00It is imperative to underscore the critical importance of proactive engagement with one’s healthcare plan, particularly during annual enrollment periods. The utilization of the Medicare Plan Finder tool is not merely advisable - it is a fundamental component of responsible health management. Furthermore, the eligibility criteria for the Low-Income Subsidy program must be rigorously evaluated by all qualifying beneficiaries, as the financial relief afforded is both substantial and underutilized. It is incumbent upon each individual to advocate for their own health equity by seeking assistance through State Health Insurance Assistance Programs, which have demonstrably aided over twelve million individuals in 2024 alone. The complexity of the system does not absolve the individual of their duty to navigate it with diligence and precision.

Howard Esakov

February 7, 2026 AT 11:46Oh, so now the government’s gonna ‘negotiate’ prices? 🤡 Like they didn’t spend 30 years letting PBMs and manufacturers collude? And you think a 25% cut is gonna fix this? Nah. They’ll just cut corners. More shortages. More panic. More ‘oops, your drug’s gone’ emails.

Meanwhile, the same people who made billions off this mess are gonna cry ‘unfair seizure’ - while still taking their $10M bonuses.

Meanwhile, I’m still paying $40 for metformin. Thanks, America. 😎

Kathy Scaman

February 7, 2026 AT 20:14I used to think generic = cheap. Now I know it means ‘hidden in plain sight.’

My cousin’s 78-year-old neighbor pays $0 for her meds because she’s on LIS. I didn’t even know that was a thing. So I called my state’s SHIP. They walked me through it. Now I help my friends fill out the forms.

It’s not sexy. But it saves lives.