Smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer. If you’ve smoked for years-even if you quit-you’re at high risk. But here’s the good news: low-dose CT screening can find lung cancer early, when it’s most treatable. This isn’t a guess. It’s backed by massive studies, real patient outcomes, and updated national guidelines. The question isn’t whether you should get screened. It’s whether you qualify-and if you do, what happens next.

Who Qualifies for Low-Dose CT Screening?

You don’t need to be a heavy smoker for years to be at risk. The rules changed in 2021, and now more people are eligible than ever before. If you’re between 50 and 80 years old, and you’ve smoked at least 20 pack-years, you qualify. A pack-year means smoking one pack a day for a year. So, two packs a day for 10 years? That’s 20 pack-years. Or one pack a day for 20 years. Same thing.

And it doesn’t matter if you quit. As long as you stopped smoking within the last 15 years, you’re still in the group that benefits from screening. Once you’ve been smoke-free for 15 years or more, screening stops. Same if you have other serious health problems that make surgery risky or unlikely to help.

This expansion matters. Before 2021, you needed 30 pack-years and had to be at least 55. Now, millions more people-especially younger smokers and women-are included. The USPSTF says this change will save thousands of lives each year.

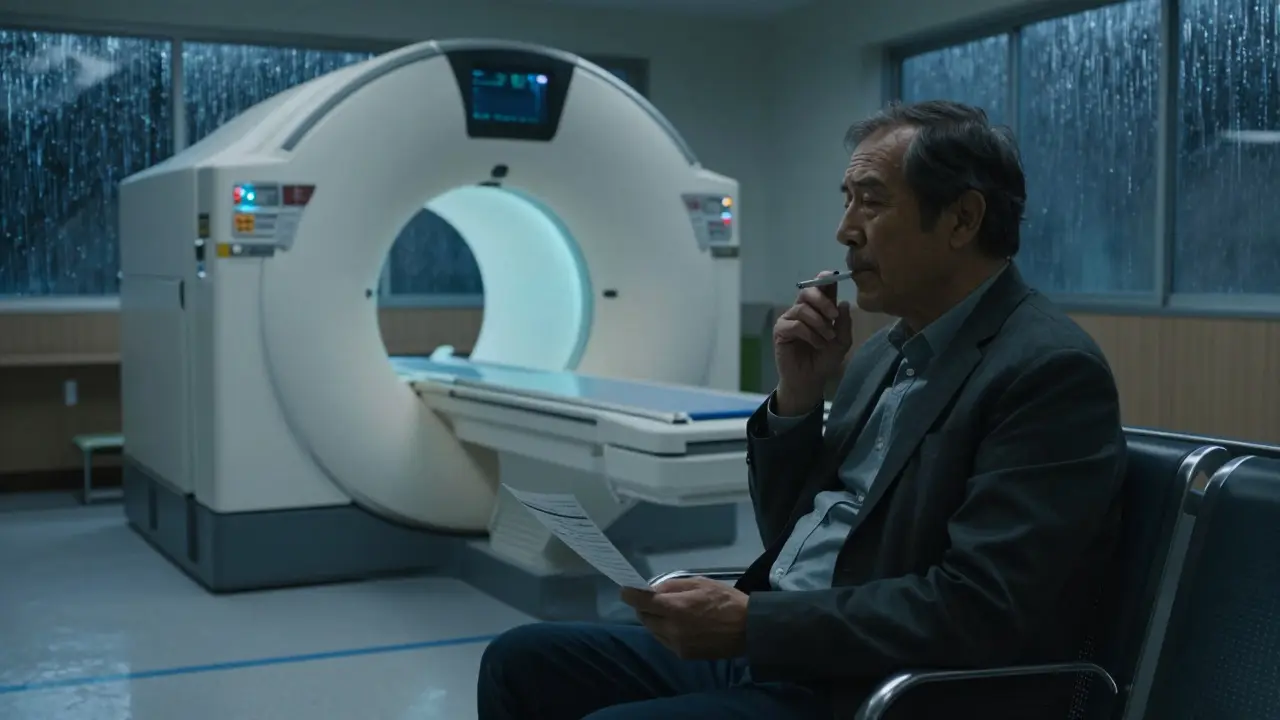

How Does Low-Dose CT Work?

It’s quick. You lie on a table. The machine spins around you. It takes pictures of your lungs using far less radiation than a regular CT scan-about 1.5 millisieverts. That’s less than half the radiation of a standard chest CT, and close to what you’d get from a mammogram. The whole thing takes under 10 minutes. No needles. No fasting. No prep.

The scan finds tiny nodules-small spots-that might be cancer. Most are harmless. But some aren’t. That’s why the scan is done every year, not just once. The goal isn’t to find cancer every time. It’s to catch it early enough to remove it before it spreads.

Doctors use something called Lung-RADS to rate what they see. It’s a simple scale from 1 to 4. Category 1 means nothing found. Category 2 means benign findings-like scars from old infections. Category 3 means probably harmless, but needs another scan in 6 months. Category 4 means something suspicious. That’s when you get more tests: a biopsy, maybe a PET scan, or closer follow-up.

The Real Benefits: Saving Lives

The National Lung Screening Trial in 2011 was the turning point. It compared low-dose CT to chest X-rays in over 50,000 high-risk smokers. The results were clear: LDCT cut lung cancer deaths by 20%. That’s not a small number. It means for every 1,000 people screened yearly for 10 years, about 3 to 4 deaths are prevented.

One woman in Manchester, 53, had smoked a pack a day since she was 18. She quit at 48 but kept her annual scan. At 53, the scan found a 6mm nodule. It was stage 1 lung cancer. Surgery removed it. Five years later, she’s cancer-free. She told her story on the American Lung Association’s site: "I didn’t feel sick. I had no symptoms. If I hadn’t gotten screened, I wouldn’t have known until it was too late."

Modeling studies suggest the expanded guidelines could prevent up to 15,000 lung cancer deaths a year in the U.S. alone. That’s more than the population of a small city.

The Downsides: False Alarms and Anxiety

But it’s not perfect. About 1 in 7 people who get a low-dose CT will get a false positive-the scan shows something that looks like cancer but isn’t. That means more tests. More scans. Sometimes, a biopsy. And a lot of stress.

A 2022 study found that 37% of people with false positives had moderate to severe anxiety that lasted over six months. Some people avoid future screenings because of it. That’s why the pre-screening talk is so important. Your doctor needs to explain: yes, this saves lives. But yes, it also leads to unnecessary procedures sometimes.

Overdiagnosis is another concern. Some cancers found are so slow-growing they’d never cause harm. But once you see it on a scan, you’re likely to treat it. That means surgery, radiation, or chemo for something that might not have needed it.

And there’s radiation-even if it’s low. Do it every year for 10 years? That’s 15 millisieverts total. Still far below dangerous levels, but not zero. For most people, the benefit outweighs this risk. But it’s something to discuss.

Who’s Getting Screened-and Who’s Not?

Here’s the ugly truth: most eligible people aren’t getting screened. In 2022, only 8.3% of those who qualified actually had a low-dose CT. That’s up from 5.7% in 2020, but still way too low.

Why? Three big reasons. First, your doctor didn’t bring it up. In surveys, 42% of eligible patients said no one ever told them they qualified. Second, they didn’t know they were eligible. That’s 29%. Third, transportation. People in rural areas or without cars can’t get to the nearest accredited center. One Reddit user in Ohio said he drives 127 miles each way.

Black Americans are 20% less likely to be screened than white Americans-even though they have higher lung cancer rates. That’s a gap that needs fixing.

Health systems that do it right-like academic hospitals-have nurse navigators who call patients, schedule scans, and track results. They use electronic alerts to flag eligible patients. They get screening rates up to 40%. Community clinics? Often under 10%.

What Happens After the Scan?

If your scan is clean (Lung-RADS 1 or 2), you come back next year. No big deal. If it’s category 3, you’ll get another scan in 6 months. That’s not a diagnosis. It’s a watch-and-wait.

If it’s category 4, you’ll be referred to a lung specialist. They’ll order more imaging. Maybe a biopsy. If cancer is confirmed, treatment starts fast. Stage 1 lung cancer has a 90% five-year survival rate when caught early. Stage 4? That drops to under 10%.

Medicare covers it-but only if you’ve had a shared decision-making visit with your provider. That means you and your doctor talked about the risks and benefits. You can’t just walk in and ask for it. You need an order.

What’s New in 2026?

Technology is improving. In 2023, the FDA approved the first AI tool for LDCT analysis-LungAssist by VIDA Diagnostics. In trials, it cut false positives by 15.2%. That means fewer people get scared for no reason.

Doctors are also starting to use smarter risk models. The PLCOm2012 tool doesn’t just look at pack-years. It adds in family history, breathing problems, education level, and even where you lived. That helps find the people who need it most.

And the number of accredited centers is growing. As of late 2023, there are over 1,800 ACR-accredited screening sites across the U.S. But access is still uneven. If you’re unsure where to go, call your local hospital or ask your doctor for a referral to a certified center.

What Should You Do Now?

If you’re between 50 and 80 and have smoked 20 pack-years or more, talk to your doctor. Don’t wait for them to bring it up. Say: "I’m eligible for lung cancer screening. Can we discuss low-dose CT?"

If you’re still smoking, quitting is the best thing you can do. But don’t wait to quit before getting screened. Screening saves lives whether you quit or not.

If you’re over 80 or quit over 15 years ago, screening isn’t recommended. But if you’re unsure, talk to your doctor. Some people with high-risk jobs (like asbestos exposure) or family history may still benefit.

And if you’re worried about cost? Medicare covers it. Most private insurers do too. No copay if you meet the criteria.

Final Thoughts

Lung cancer kills more people than breast, colon, and prostate cancer combined. And it often shows no symptoms until it’s too late. Low-dose CT screening is the only tool we have that’s proven to change that. It’s not a magic bullet. It has risks. But for the right people, it’s life-saving.

Don’t let fear stop you. Don’t wait for symptoms. If you qualify, get screened. One scan could mean you’re around to see your grandkids grow up.

Who should get low-dose CT screening for lung cancer?

People aged 50 to 80 who have smoked at least 20 pack-years and currently smoke or quit within the last 15 years. A pack-year means smoking one pack a day for one year-for example, two packs a day for 10 years. Screening stops after 15 years of not smoking or if other health issues make treatment unlikely to help.

Is low-dose CT the same as a regular CT scan?

No. Low-dose CT uses about 1.5 millisieverts of radiation, which is much less than a standard chest CT (7-8 millisieverts). It’s designed specifically for lung screening-faster, lower radiation, and focused only on the lungs. It doesn’t use contrast dye or require fasting.

What if the scan shows something abnormal?

Most findings aren’t cancer. About 13.9% of scans show something that needs follow-up, but only about 1 in 10 of those turn out to be cancer. If the scan is flagged as Lung-RADS 3 or 4, you’ll get another scan in 6 months or be referred for a biopsy. Don’t panic-this is part of the process.

Does Medicare cover lung cancer screening?

Yes. Medicare covers annual low-dose CT screening for people aged 50-77 who meet the smoking criteria, as long as they’ve had a shared decision-making visit with their provider. No copay is required if you’re enrolled in Medicare Part B.

Can I get screened if I never smoked but have a family history of lung cancer?

Current guidelines only cover smokers and recent former smokers. Family history alone doesn’t qualify you for screening under USPSTF or Medicare rules. But if you have other risk factors-like exposure to radon, asbestos, or air pollution-talk to your doctor. Research is ongoing to expand criteria.

How often should I get screened?

Once a year, as long as you still meet the eligibility criteria. Stopping smoking doesn’t mean you stop screening immediately-you keep getting screened for up to 15 years after quitting. After that, or if your health changes significantly, screening is no longer recommended.

Mike P

January 23, 2026 AT 03:41Yo, if you’re still smoking and think you’re invincible, you’re not. This screening isn’t a favor-it’s your last shot at not becoming a statistic. I’ve seen too many guys in my VA group die slow, ugly deaths because they waited for symptoms. Don’t be that guy.

Ryan Riesterer

January 23, 2026 AT 18:53The 2021 USPSTF guideline revision expanded eligibility to include 20 pack-years and lowered the age threshold to 50, which significantly increases population-level sensitivity. The NLSCT demonstrated a 20% reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality via LDCT versus CXR, with a number needed to screen of approximately 320 to prevent one death over 10 years.

Neil Ellis

January 25, 2026 AT 04:35Man, I used to think lung cancer was just a ‘smoker’s disease’-until my aunt got diagnosed at 52, never smoked a day in her life. Radon in her basement, probably. The point is, screening isn’t just for the ‘bad choices’ crowd. It’s for anyone who’s lived long enough to have risk factors. We need to stop stigmatizing and start saving lives.

Lauren Wall

January 26, 2026 AT 09:46So let me get this straight-you want me to get scanned every year for a decade just because I smoked in college? Yeah, no.

Rob Sims

January 27, 2026 AT 08:40Oh great, another government-mandated scan. Next they’ll be forcing us to get MRI brain scans because we’ve seen a TikTok video. Let’s just let nature take its course. People die. It’s called life.

Tatiana Bandurina

January 29, 2026 AT 02:08False positives are the real problem. You get a 3, you panic, you get a biopsy, you lose your job because your insurance flags you as ‘high risk,’ then they tell you it was just scar tissue. Who’s paying for the therapy after that? Not the CDC.

shivani acharya

January 30, 2026 AT 23:16They’re using this to push Big Pharma’s agenda. LDCT? Sure. But what about the AI tools? VIDA Diagnostics? That’s owned by a pharmaceutical subsidiary. They want you scared, scanning, and on chemo. They don’t want you to know about the 15% of cancers that are indolent. They profit from fear. Wake up.

Kenji Gaerlan

February 1, 2026 AT 03:02im 52 and smoked 2 packs a day for 12 yrs so thats 24 pack years right? so i qualify? also where do i even go for this? my doc just shrugs

Jasmine Bryant

February 1, 2026 AT 21:35Hey, I’m a nurse in rural Kansas and we’ve been pushing this hard. We’ve got a mobile van that goes to towns 50+ miles out. It’s not perfect, but we’ve gotten 22 people screened in the last 6 months. If you’re eligible and don’t know where to go-DM me. I’ll help.

Daphne Mallari - Tolentino

February 3, 2026 AT 02:44It is, of course, both ethically and epidemiologically imperative to acknowledge the disproportionate burden of lung cancer among marginalized populations. The 20% disparity in screening rates between Black and white Americans reflects not merely access issues, but systemic failures in physician-patient communication and institutional trust. We must address this with structural interventions, not merely individual outreach.

Philip House

February 3, 2026 AT 10:47They say screening saves lives. But what if the real problem is that we’re medicating the symptom instead of curing the cause? Why not just ban cigarettes? Why not make nicotine a controlled substance? We’re treating the fallout of capitalism’s addiction machine, not the machine itself.

arun mehta

February 5, 2026 AT 08:35Thank you for this comprehensive breakdown 🙏. As someone from India, I see how few here even know about LDCT. My uncle, a 30-pack-year smoker, passed away last year-never screened. Let’s spread awareness. Maybe one scan can save a father, a brother, a friend. 🌍❤️

Liberty C

February 6, 2026 AT 22:28It’s fascinating how we’ve turned medical screening into a moral performance. You’re not ‘responsible’ if you skip it-you’re just statistically unlucky. Meanwhile, the same people who champion this screening won’t touch a single vape ad. Cognitive dissonance at its finest.

Akriti Jain

February 7, 2026 AT 22:31They say radiation is low. But what if it’s cumulative? What if the machines are calibrated wrong? What if they’re using the same scans for other purposes? I read a whistleblower report-there’s a backdoor in the VIDA software. They’re storing lung data for facial recognition training. You think that’s a coincidence?

Sarvesh CK

February 8, 2026 AT 16:04While the clinical efficacy of low-dose CT screening is well-documented, we must also consider the philosophical dimension of preventive medicine. To screen is to assume that life can be prolonged through surveillance, yet this may inadvertently diminish the quality of lived experience. The anxiety induced by false positives, the medicalization of normal aging, and the commodification of health-these are not trivial consequences. Perhaps the deeper question is not whether we should screen, but whether we are ready to bear the emotional weight of knowing too much, too early.

Ryan Riesterer

February 8, 2026 AT 18:58Regarding the PLCOm2012 model: it integrates non-smoking risk factors such as COPD history, educational attainment, and environmental exposures (e.g., radon, occupational carcinogens), which improves risk stratification beyond pack-years alone. This may allow for personalized screening intervals rather than universal annual scans, reducing unnecessary exposure and cost.