Why does a bottle of insulin cost $30 in Germany but $300 in the U.S.? Or why can you buy Ozempic for under $50 in Japan but over $1,000 in America? The answer isn’t about quality, supply, or science-it’s about policy. Drug prices vary wildly across countries, not because one nation is more efficient or greedy, but because each has built its own system to control-or not control-what patients pay.

How the U.S. Compares to Other Rich Countries

If you look only at list prices for brand-name drugs, the U.S. looks like an outlier. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Americans pay nearly 2.8 times more than other OECD countries for the same brand-name medicines. For drugs like Jardiance, the gap is even worse: Medicare’s negotiated price is almost four times what Japan pays. The same pattern holds for Entresto, Enbrel, and Eliquis. In nearly half the cases studied, U.S. prices exceeded international prices by more than three times.

But here’s the twist: when you factor in net prices-what actually gets paid after rebates, discounts, and generics-the picture changes. A 2024 study from the University of Chicago found that when you weigh prices by how often drugs are actually prescribed, the U.S. pays 18% less than Canada, Germany, the UK, France, and Japan combined. How? Because 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generics, and those are dirt cheap. The average U.S. generic costs 67% less than the same drug abroad.

So the real story isn’t that the U.S. is the most expensive country for all drugs. It’s that it’s the most expensive for new, branded drugs-and the cheapest for generics. That’s a dual system: high prices for innovation, low prices for everything else.

Who Has the Lowest Prices? Japan and France Lead

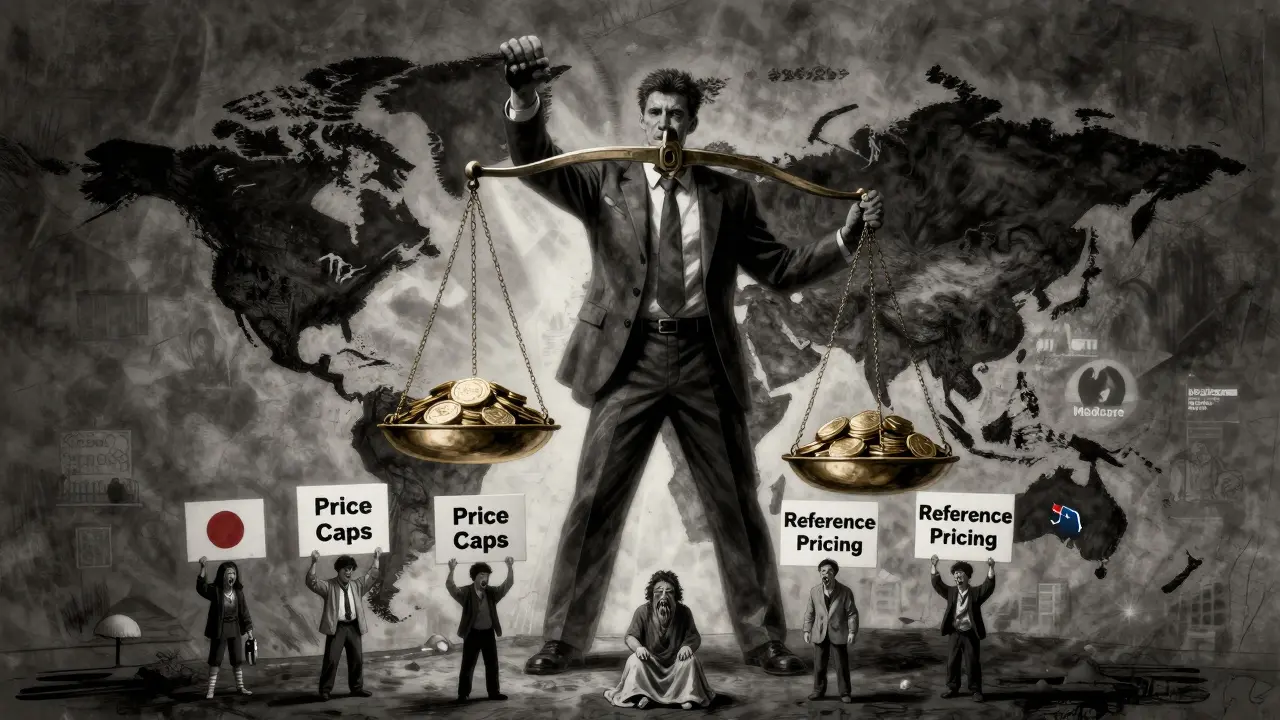

Japan and France consistently rank as the two countries with the lowest prices for brand-name drugs across nearly every category. For Jardiance, Entresto, and Imbruvica, Japan’s price is often less than half of what the U.S. charges. France doesn’t just negotiate-it sets hard price caps. If a drug is too expensive, it simply won’t be covered by public insurance. That’s why you rarely hear about French patients going bankrupt from medication costs.

Australia also stands out. For drugs like Eliquis and Xarelto, Australia’s prices are the lowest among major developed nations. Why? Because it uses external reference pricing: it looks at what other countries pay and sets its own price at or below the median. If a drug costs $100 in Germany and $80 in Canada, Australia will cap it at $80. Simple. Effective. And it works for both new and older drugs.

Canada, Germany, and the UK: The Middle Ground

Canada and Germany are often seen as expensive-but they’re not. They’re just not as cheap as Japan. Canada uses a mix of negotiation and price controls. Its Patented Medicine Prices Review Board sets maximum prices based on what’s paid in other countries. Germany uses reference pricing: if you have a group of similar drugs (say, five different statins), the government picks the cheapest one as the benchmark. If you want a more expensive version, you pay the difference out of pocket.

The UK’s NHS is similar. It doesn’t just negotiate prices-it threatens to block access if a company won’t lower its price. That’s why so many new cancer drugs come to the UK first: companies know the NHS will pay if the price is right. If not? The drug sits on the shelf.

For patients, this means fewer surprises. No surprise bills. No pharmacy counters where you’re handed a $2,000 prescription and told to choose between food and medicine.

What About the Rest of the World?

The global picture is even wilder. A 2024 study in JAMA Health Forum looked at 549 essential medicines across 72 countries. When adjusted for how much people actually earn, prices ranged from 18% of Germany’s cost in Lebanon to 580% in Argentina. That’s not inflation-it’s broken systems. In Lebanon, people can’t afford drugs even if they’re cheap. In Argentina, prices are artificially high because of currency controls and import restrictions.

In the Americas, median prices are 165% of Germany’s baseline. In Europe, they’re 139%. In the Western Pacific (which includes Japan, Australia, and South Korea), they’re the lowest at 132%. Why? Because those countries have centralized buying power. They don’t let 500 private insurers each negotiate separately. One buyer. One price. That’s how you drive costs down.

China’s story is telling. In 2018, it launched a national drug negotiation program. It brought down prices for cancer drugs by up to 70% in just two years. India, too, has become a global hub for cheap generics-producing 20% of the world’s medicines by volume. But India doesn’t export many of its cheapest drugs domestically. The poor there still struggle to afford even generic versions because of distribution gaps.

How the U.S. Is Changing (Slowly)

The U.S. didn’t always have this system. Until 2022, Medicare was legally banned from negotiating drug prices. Insurers and pharmacies negotiated on their own, and manufacturers could charge whatever they wanted. The result? The top 10 selling Medicare Part D drugs in 2022 cost $4.6 billion just for Ozempic alone.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 changed that. For the first time, Medicare can negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs. The first round was announced in 2023, with prices set to take effect in 2025. Those 10 drugs include Jardiance, Eliquis, and Ozempic. The negotiated prices are still higher than in Japan or France-but they’re a start.

By February 1, 2025, Medicare will name the next 15 drugs up for negotiation. The goal? To bring U.S. prices closer to global norms. Experts say if this works, it could cut U.S. drug spending by $100 billion over the next decade.

Why This Matters for Patients

It’s not just about dollars. It’s about choices. In countries with price controls, patients don’t skip doses because they can’t afford their meds. In the U.S., one in four adults reports cutting pills in half or going without because of cost. That’s not a personal failure-it’s a system failure.

And it’s not just the poor. Even middle-class families with insurance face high deductibles and copays. A $500 copay for a diabetes drug isn’t rare. That’s not “insurance.” That’s a payment plan disguised as coverage.

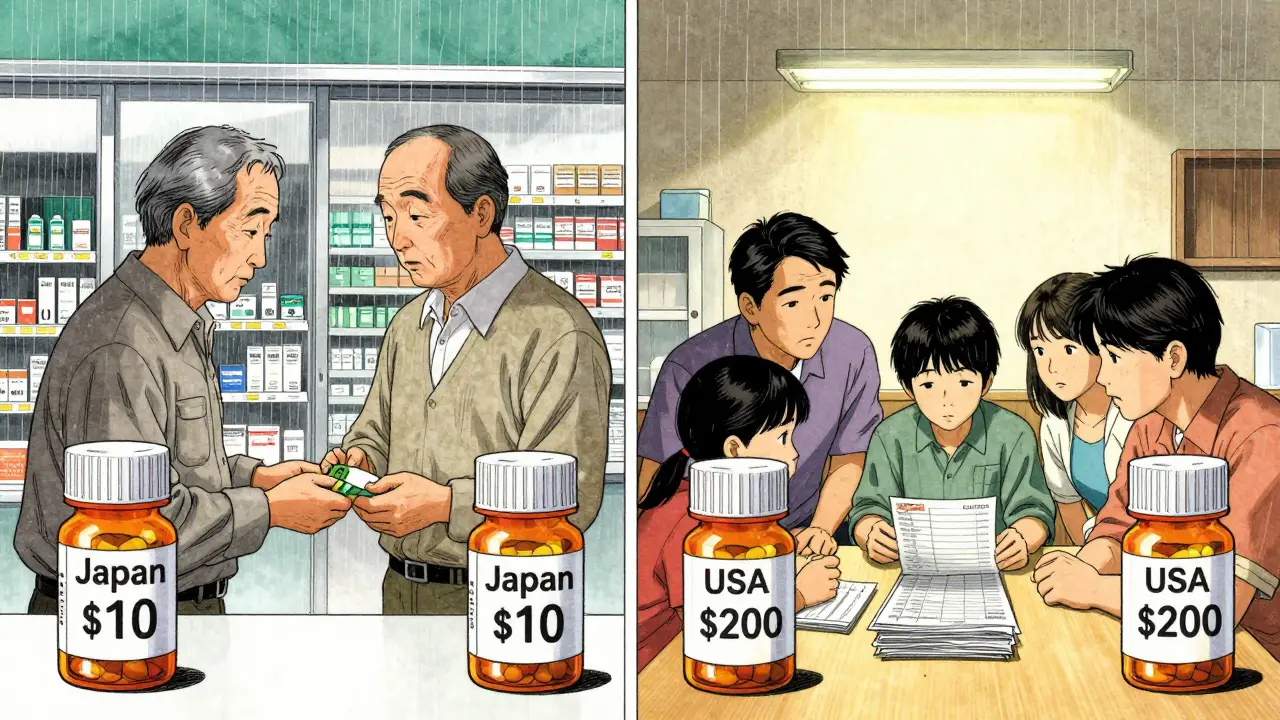

Meanwhile, in Japan, a 75-year-old with type 2 diabetes pays $10 a month for the same drug. In Germany, it’s $15. In the U.S.? It’s $200-even with Medicare.

What’s the Real Trade-Off?

Some argue that high U.S. prices fund innovation. That’s the theory: drug companies charge more here so they can afford to develop new treatments. But the data doesn’t fully back that up. The U.S. spends more on drugs than the next 10 countries combined-and yet, it doesn’t produce more breakthroughs. Most new drugs are developed by global teams, often with public funding from NIH or EU grants.

And here’s the kicker: when countries like Canada or Australia negotiate lower prices, companies still make money. They sell more volume. They keep R&D going. They just don’t charge patients the equivalent of a car payment every month.

The real trade-off isn’t innovation vs. affordability. It’s profit margins vs. human health. And right now, the U.S. is choosing the former.

What You Can Do

Even if you’re stuck in the U.S. system, you’re not powerless. Here’s what works:

- Always ask for the generic. Even if your doctor doesn’t suggest it, it’s often 80% cheaper.

- Use GoodRx or RxSaver. These apps show you the lowest cash price at nearby pharmacies-sometimes lower than your insurance copay.

- Check if your drug is on Medicare’s negotiation list. If it is, prices will drop in 2025. Plan ahead.

- Consider mail-order pharmacies. They often have lower prices and free shipping.

- Ask your pharmacist about patient assistance programs. Drugmakers have them-sometimes you just have to ask.

It’s not perfect. But it’s something. And it’s more than most people do.

What’s Next?

By 2026, we’ll know if Medicare’s negotiation experiment works. If prices drop and companies don’t collapse, other countries will take notice. If prices stay high and innovation slows, the U.S. will face even louder calls for reform.

One thing’s clear: the old model-where the U.S. pays whatever it’s told-is ending. Patients are tired. Politicians are listening. And the rest of the world? They’ve been doing this for decades.

Why are drug prices so much higher in the U.S. than in other countries?

The U.S. doesn’t regulate drug prices like most other countries. Instead, drugmakers set list prices, and private insurers negotiate discounts behind closed doors. Because Medicare was banned from negotiating until 2022, there was no strong buyer to push prices down. Other countries use government negotiation, price caps, or reference pricing to keep costs low. The U.S. system favors corporate profits over patient affordability.

Are generic drugs cheaper in the U.S. than elsewhere?

Yes. The U.S. has the cheapest generic drugs in the world. On average, U.S. generics cost 67% less than the same drugs in other developed countries. This is because of strong competition among generic manufacturers, aggressive FDA approval processes, and large-scale bulk purchasing by pharmacies and insurers. That’s why 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generics-they’re affordable and widely available.

Which countries have the lowest drug prices?

Japan and France consistently have the lowest prices for brand-name drugs. Australia is also among the cheapest, especially for newer medications like Eliquis and Xarelto. These countries use external reference pricing-setting their prices based on what other nations pay. Germany and Canada are slightly higher but still far below U.S. levels. All of them negotiate or cap prices, unlike the U.S., which only recently began doing so.

How does Medicare’s new drug negotiation program work?

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, Medicare can now negotiate prices for up to 10 high-cost drugs each year starting in 2025. The first 10 drugs include Jardiance, Eliquis, and Ozempic. Medicare will set a price based on what other countries pay, the drug’s cost to produce, and how much it’s used. If a company refuses to agree, it faces a tax penalty. This is the first time the U.S. government has directly controlled drug prices on a large scale.

Can I save money on prescriptions if I live in the U.S.?

Yes. Use GoodRx or RxSaver to compare cash prices at local pharmacies-sometimes they’re cheaper than your insurance copay. Always ask for the generic version. Ask your pharmacist about manufacturer coupons or patient assistance programs. Consider mail-order pharmacies for maintenance meds. And if you’re on Medicare, check if your drug is on the negotiation list-prices will drop in 2025.

Do high U.S. drug prices fund innovation?

It’s a common argument, but the evidence is mixed. While U.S. companies do spend more on R&D, most breakthrough drugs are developed with public funding (like NIH grants) and global collaboration. Countries with lower drug prices, like Japan and Germany, still produce major innovations. The real difference is that other countries cap profits so patients don’t pay the bill-while the U.S. lets companies charge more, and patients bear the cost.

Haley Parizo

January 3, 2026 AT 04:20Let’s be real-the U.S. isn’t broken, it’s designed this way. Pharma isn’t a public utility, it’s a profit engine, and we’re the fuel. Other countries negotiate because they see healthcare as a right. We treat it like a luxury auction. And guess who wins? The shareholders. Not the diabetic grandma paying $200 for insulin. This isn’t capitalism-it’s cannibalism dressed in a lab coat.

Ian Ring

January 5, 2026 AT 02:21Interesting analysis-though I’d argue the UK’s NHS model is more sustainable than most assume. Yes, delays happen, but the trade-off is predictable costs. I’ve seen friends in Germany pay €5 for a month’s supply of blood pressure meds. Here? £40, and that’s with the NHS. The U.S. system feels like a casino where the house always wins… and patients are the ones losing their savings. 😔

erica yabut

January 5, 2026 AT 02:50Oh, sweet mercy, the U.S. is the only country that lets corporate vultures turn life-saving molecules into Wall Street derivatives. You think Japan’s ‘price cap’ is draconian? Try living under a system where your kidney function is literally priced in dollars per milliliter. The fact that Americans still believe in ‘innovation funding’ is the most tragic form of Stockholm Syndrome I’ve ever witnessed. We’re not paying for science-we’re paying for shareholder dividends disguised as R&D.

And don’t even get me started on ‘generics.’ Sure, they’re cheap-but only because Big Pharma deliberately lets them flood the market after patent cliffs to crush competition. It’s not a win-it’s a trap. The system is rigged, and we’re the ones holding the bag.

Vincent Sunio

January 5, 2026 AT 08:43There is a fundamental flaw in the assertion that the U.S. pays less on a net-price basis. The study referenced employs a weighted average methodology that obscures the reality of out-of-pocket expenditures for non-generic medications. Moreover, the assumption that ‘90% of prescriptions are generics’ mitigates systemic cost is misleading; it ignores the disproportionate burden on patients requiring biologics, oncology agents, or rare-disease therapies. The data does not support the conclusion; it merely recontextualizes the problem.

Furthermore, the notion that ‘other countries don’t innovate’ is empirically false. The majority of first-in-class drugs originate from U.S.-based institutions, but their commercialization is globally distributed. The U.S. bears the R&D cost; others free-ride on price controls. This is not a market failure-it is a strategic asymmetry.

Kerry Howarth

January 6, 2026 AT 09:59You don’t have to accept the system as it is. Ask for generics. Use GoodRx. Talk to your pharmacist. These are real tools that work. I helped my mom save $1,200/year just by switching to a mail-order pharmacy and using coupons. It’s not perfect, but it’s something. Small steps add up.

Shruti Badhwar

January 7, 2026 AT 06:34India produces 20% of the world’s generics-but domestic access remains a crisis. Why? Because the supply chain is broken. Rural pharmacies can’t afford to stock them. Middlemen inflate prices. And the government doesn’t enforce price ceilings on distribution. The problem isn’t manufacturing-it’s logistics and corruption. We need the same centralized procurement systems seen in Australia or Germany. Otherwise, cheap drugs mean nothing if they never reach the people who need them.

Also, let’s stop romanticizing Japan. Their system works because they have a homogenous population, strong public trust, and zero lobbying power from pharma. Can we replicate that here? Maybe not. But we can steal the policy tools.

Brittany Wallace

January 8, 2026 AT 01:47I’ve lived in both the U.S. and Germany. In Berlin, my dad got his heart meds for €8 a month. Here? $220. And I’m not even on Medicare. It’s not about ‘innovation’-it’s about who gets to live. I cried the first time I saw my friend choose between her insulin and her rent. That’s not a policy debate. That’s a moral emergency.

We’re not just arguing about prices. We’re arguing about dignity. And honestly? I’m tired of pretending this is a hard problem. It’s not. We just haven’t chosen to fix it yet.

Michael Burgess

January 9, 2026 AT 15:23Here’s the wild part: the U.S. is basically the world’s drug lab. We pay the high price so companies can afford to test crazy new stuff-then everyone else buys the leftovers at a discount. It’s like we’re the ones footing the bill for global medical progress. Not saying it’s fair-but it’s the reality. The Inflation Reduction Act is trying to rebalance that. Maybe it’ll work. Maybe not. But at least someone’s trying.

Also, GoodRx saved my ass last year. $400 down to $12 for my thyroid med. Never thought I’d say this, but… thank you, internet.

Liam Tanner

January 9, 2026 AT 18:28For anyone thinking this doesn’t affect you: it will. One day, you or someone you love will need a drug that costs more than your car payment. And then you’ll realize-this isn’t a ‘them’ problem. It’s an ‘us’ problem. And we’re all waiting for someone else to fix it.

Palesa Makuru

January 11, 2026 AT 00:10Ugh, I’m so tired of Americans acting like they’re the only ones who’ve ever had to choose between medicine and food. In South Africa, we’ve been doing this for decades-because our government is corrupt and our healthcare is privatized too. At least you guys have GoodRx. We have nothing. And you’re still whining? Get a grip.

Hank Pannell

January 12, 2026 AT 02:33Let’s deconstruct the innovation myth. The NIH funded 70% of the foundational research behind the top 10 drugs on Medicare’s negotiation list. Pharma didn’t invent them-they acquired them, repackaged them, and slapped on a 500% markup. The real innovation is in the pricing algorithms, not the molecules. And if you think Japan’s system kills innovation, explain why they’re still leading in oncology and AI-assisted diagnostics. They’re not stagnant-they’re strategic.

Also, the term ‘net price’ is a corporate euphemism. It’s the price after rebates. But rebates go to insurers and PBMs, not patients. So yes, the system looks cheaper on paper-but your deductible? Still sky-high. That’s not transparency. That’s obfuscation.

And don’t get me started on ‘reference pricing.’ Australia doesn’t just look at Germany’s price-they look at what the drug *costs to produce*. That’s radical. We look at what the CEO’s yacht costs.

Lori Jackson

January 12, 2026 AT 15:32It’s pathetic. People still think this is about ‘affordability.’ No. It’s about moral bankruptcy. You let a company charge $1,000 for a drug that costs $2 to make, and you call it ‘free enterprise.’ Meanwhile, children in rural Alabama are rationing insulin. This isn’t capitalism-it’s feudalism with a pharmacy card.

And don’t give me that ‘innovation’ nonsense. The last time I checked, the NIH didn’t need Wall Street’s permission to fund research. But somehow, when it comes to pricing, we’re all supposed to be grateful for crumbs. Wake up. This isn’t an economic issue. It’s a crime against humanity.

Wren Hamley

January 14, 2026 AT 08:21Just read the JAMA study again. The 18% lower net cost? That’s because 90% of scripts are generics. But here’s the catch: the 10% that aren’t? They’re the ones that kill you if you skip them. So yeah, you save on metformin-but what about your cancer drug? That’s where the system collapses. And guess who pays? The people who can’t afford to be ‘smart shoppers.’

Also, ‘Ask for generics’ is great advice… if your doctor doesn’t think your brand-name drug is ‘more effective.’ Spoiler: they’re usually wrong. But they’re paid to push the expensive stuff. The system is rigged.

Sarah Little

January 15, 2026 AT 16:03Wait-so you’re saying the U.S. is cheaper because generics are cheap? But what about the patients who need biologics? Or the ones with autoimmune diseases? Their meds aren’t generic. And they’re priced like luxury watches. This argument feels like a distraction. The problem isn’t the 90%-it’s the 10% that destroy lives.