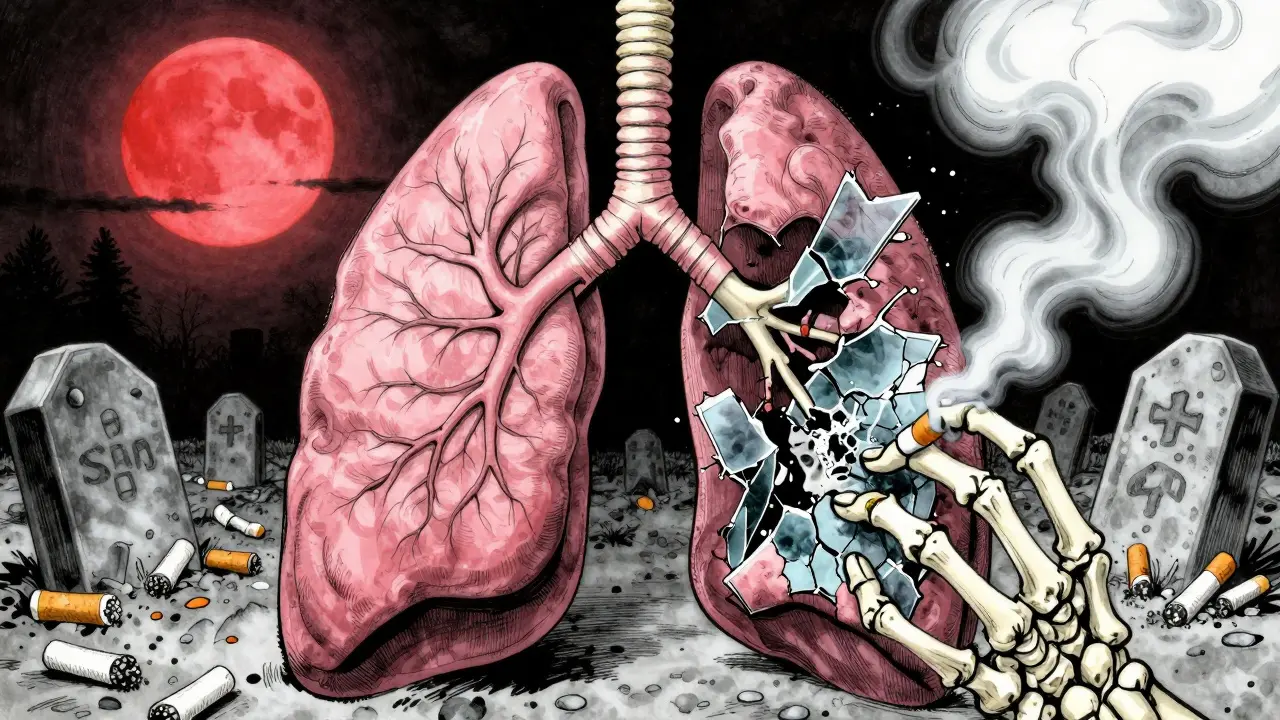

When your lung suddenly stops working right - not from a cough or cold, but from air leaking where it shouldn’t be - you don’t get time to wait it out. A pneumothorax, or collapsed lung, can turn deadly in minutes. It’s not rare. Around 1 in 5,000 people in the UK will experience it at some point. And if you’re a tall, young man who smokes, your risk jumps dramatically. The good news? If you know the signs and act fast, survival rates are high. The bad news? Waiting even 30 minutes can make things much worse.

What Happens When Your Lung Collapses

Your lungs sit inside your chest, wrapped in a thin, slippery sac called the pleura. Normally, the space between your lung and chest wall is empty - just a tiny bit of fluid to help things slide smoothly. When air gets in there - from a burst blister on the lung, a broken rib, or even a medical procedure - it pushes the lung inward like a balloon losing air. That’s pneumothorax. The lung can’t expand fully when you breathe, so oxygen drops fast. There are four main types. Primary spontaneous happens in otherwise healthy people, often tall, lean young men under 30. Secondary spontaneous occurs with existing lung disease - COPD, cystic fibrosis, or pneumonia. Traumatic pneumothorax comes from car crashes, stab wounds, or broken ribs. Iatrogenic means it was caused by a doctor - maybe during a biopsy, central line placement, or even CPR. Each type needs different handling, but all demand attention.The Symptoms You Can’t Ignore

Most people don’t wake up with a collapsed lung. They’re walking, talking, maybe even laughing - then everything changes. The first sign? Sharp, stabbing chest pain on one side. Not dull. Not achy. It feels like someone just jammed a knife between your ribs. It gets worse when you breathe in deep or cough. That’s pleuritic pain, and it’s the most reliable clue. Right after the pain comes shortness of breath. Not the kind you feel after climbing stairs. This is breathing hard while sitting still. If you can’t finish a sentence without gasping, that’s a red flag. In severe cases, oxygen levels drop below 90% - your lips or fingertips may turn blue. That’s cyanosis. It means your body isn’t getting enough oxygen. Other signs include a fast heartbeat - over 130 beats per minute - and feeling lightheaded. You might feel pressure in your shoulder, especially on the same side as the pain. That’s because the nerves from your lung and shoulder share pathways. Doctors call this referred pain. Tension pneumothorax is the nightmare scenario. Air keeps building up, pushing your heart and other lung to the other side. Your blood pressure crashes. You start sweating. Your neck veins bulge. Your trachea shifts. This isn’t just an emergency - it’s a race against time. Survival depends on acting before you lose consciousness.How Doctors Diagnose It

In the ER, they don’t waste time. If you’re unstable - low blood pressure, fast heart rate, struggling to breathe - they don’t wait for an X-ray. They stick a needle into your chest right away to let the air out. That’s needle decompression. It’s not a test. It’s treatment. If you’re stable, they’ll do a chest X-ray. It’s quick, cheap, and catches most cases. But it’s not perfect. If you’re lying down - like after a car crash - up to 60% of small collapses can be missed. That’s why many hospitals now use ultrasound. A trained emergency doctor can spot the “lung point” - the exact spot where the lung stops moving - with over 94% accuracy. It’s faster than waiting for the X-ray machine. CT scans are the gold standard. They show even tiny leaks, as small as 50 milliliters of air. But they’re not used first. Too much radiation. Too slow. Only if the X-ray is unclear or the patient has complex injuries do they go there. Blood tests help too. Low oxygen, high carbon dioxide - those show up in arterial blood gases. It’s not the diagnosis, but it tells you how badly your body is struggling.

Emergency Treatment - What Actually Happens

If it’s a small collapse - less than 2 cm of air on the X-ray - and you’re breathing okay, they might just watch you. Give you oxygen through a mask (10-15 liters per minute), and let your body absorb the air naturally. About 8 out of 10 people recover this way in two weeks. If it’s bigger, or you’re struggling to breathe, they’ll remove the air. Needle aspiration is the first try. A thin tube is inserted into your chest, and air is sucked out. It works about 65% of the time. If it fails, they go straight to a chest tube. A thicker tube (usually 28F) is placed between your ribs and connected to a suction device. This pulls the air out and lets your lung re-expand. Success rate? Over 90%. Tension pneumothorax? No waiting. No X-ray. No debate. Needle decompression - immediately. A 14-gauge needle goes into the second rib space, right above your nipple. Air hisses out. Blood pressure rises. Pulse slows. You breathe easier. Then they follow up with a chest tube. Delaying this by even 5 minutes can kill you. For people who’ve had this before, or have lung disease, they may need surgery. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is the go-to. Small cuts, a camera, and a surgeon seals the leak with staples or removes damaged tissue. It cuts recurrence risk from 40% down to under 5%. But it’s not quick. You’re in the hospital for 2-4 days.What Happens After You Leave the Hospital

You can’t just go home and pretend nothing happened. Your lung needs time to heal. No flying for 2-3 weeks. The change in cabin pressure can make air pockets expand and cause another collapse. No scuba diving - ever - unless you’ve had surgery to prevent it. The pressure underwater is too dangerous. Smoking? Quit now. If you smoke 10 packs a year or more, your risk of another collapse is over 20 times higher than a non-smoker. Quitting cuts that risk by 77% in just one year. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a life-saving rule. You’ll need a follow-up X-ray in 4-6 weeks. About 8% of people develop delayed problems - fluid buildup, infection, or a second collapse - if they don’t get checked. Don’t skip it. If you had a secondary pneumothorax - meaning you have COPD, asthma, or another lung disease - your outlook is tougher. One in six people with this type die within a year. That’s why doctors treat it more aggressively. They don’t wait. They don’t hope. They act.

When to Call 999 - The Red Flags

You don’t need to be an expert to know when to get help. If you or someone else has:- Sudden, sharp chest pain on one side

- Difficulty breathing, even while sitting still

- Blue lips or fingertips

- Heart racing with no reason

- Can’t speak in full sentences

- Feeling dizzy or passing out

Who’s Most at Risk

Men are 6.5 times more likely than women to get a spontaneous pneumothorax. Tall people - over 70 inches - are more than three times as likely. Smoking is the biggest modifiable risk. One pack a day for 10 years? Your odds jump 22 times. Genetics play a role too. Some families have a history of lung blebs - weak spots on the lung surface that burst easily. People with COPD, emphysema, or tuberculosis are at high risk for secondary pneumothorax. Even if they’ve never had one before, a simple cough can trigger it. That’s why doctors monitor these patients closely after any respiratory infection.Can You Prevent It?

Yes - but only if you act. Stop smoking. That’s it. Nothing else comes close. No supplements. No exercises. No breathing devices. Smoking is the #1 cause of preventable pneumothorax. If you’ve had one before, talk to a thoracic surgeon. If you’ve had two on the same side, your chance of a third is over 60%. Surgery can prevent that. It’s not a big operation. It’s not risky. It’s life-changing. Don’t wait for a second collapse to take it seriously. One episode is a warning. Two is a pattern. Three? That’s a crisis.Can a collapsed lung heal on its own?

Yes, but only if it’s small and you’re otherwise healthy. For primary spontaneous pneumothorax under 2 cm, about 82% resolve on their own within two weeks with oxygen support. But if you’re short of breath, have low oxygen, or have lung disease, you need treatment - not waiting.

Is pneumothorax the same as a pulmonary embolism?

No. A pulmonary embolism is a blood clot blocking an artery in the lung. It causes sudden shortness of breath and chest pain too, but the pain is often more squeezing than stabbing. It’s also linked to recent travel, surgery, or birth control use. Pneumothorax is air in the chest cavity. They need different treatments - one needs clot-busting drugs, the other needs air removed.

How long does it take to recover from a chest tube?

Most people go home within 3-5 days after the tube is removed. Full healing takes 4-6 weeks. You’ll feel weak and sore for a while. Avoid heavy lifting, pushing, or pulling for at least a month. Return to work depends on your job - office work in 1-2 weeks, manual labor may take 6-8 weeks.

Can you fly after a pneumothorax?

No - not for at least 2-3 weeks after the lung has fully re-expanded and you’ve had a follow-up X-ray confirming it. Air expands at altitude. If any air remains in your chest, it can grow and cause another collapse mid-flight. The FAA and UK Civil Aviation Authority both require clearance from a doctor before flying.

Does stress cause pneumothorax?

No. Stress doesn’t cause air to leak from your lung. But if you’re under stress and you smoke, you’re more likely to ignore early symptoms or delay care. That’s dangerous. The real causes are smoking, lung disease, trauma, or weak spots in the lung tissue - not anxiety or pressure.